Chapter 3. Building Our Own Async Queues

Although we have explored basic async syntax and solved a problem using high-level async concepts, you still might not be completely sure of what tasks and futures really are and how they flow through the async runtime. Describing futures and tasks can be difficult to do, and they can be hard to understand. This chapter consolidates what you have learned about futures and tasks so far, and how they run through an async runtime, by walking you through building your own async queues with minimal dependencies.

This async runtime will be customizable by choosing the number of queues and the number of consuming threads that will be processing these queues. The implementation does not have to be uniform. For instance, we can have a low-priority queue with two consuming threads and a high-priority queue with five consuming threads. We will then be able to choose which queue a future is going to be processed on. We will also be able to implement task stealing, whereby consuming threads can steal tasks from other queues if their queue is empty. Finally, we will build our own macros to enable high-level use of our async runtime.

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to implement custom async queues and fully understand how futures and tasks travel through the async runtime. You will also have the skills to customize async runtimes to solve problems that are specific to you and that a standard out-of-the-box runtime environment might not be able to handle. Even if you do not want to implement your own async queues ever again, you will have a deeper understanding of async runtimes so you can manipulate high-level async crates more effectively to solve problems. You will also understand the trade-offs of async code even when implementing async code at a high level.

We begin our exploration of building async queues by defining how tasks are spawned, as task spawning serves as the entry point to the runtime. This async runtime will be customizable, allowing you to choose how many queues you have and how many consuming threads will process these queues.

Building Our Own Async Queue

In this section, we will walk through the process of building a custom asynchronous queue. If we break our implementation into steps, we will see firsthand how our futures get converted into tasks and executed.

In this example, we are building a simple asynchronous queue, and we are going to be dealing with three tasks. We will describe each task as we define it.

Before we write any code, we need the following dependencies:

[dependencies]async-task="4.4.0"futures-lite="1.12.0"flume="0.10.14"

We are using these dependencies:

async-task-

This crate is essential for spawning and managing tasks within an async runtime. It provides the core functionality needed to convert futures into tasks.

futures-lite-

A lightweight implementation of futures.

flume-

A multiproducer, multi-consumer channel that we’ll use to implement our async queue, allowing tasks to be safely passed around within the runtime. We could use

async-channelhere but are opting forflumebecause we want to be able to clone receivers, as we are going to be distributing tasks among consumers. Additionally,flumeprovides unbounded channels that can hold an unlimited number of messages and implements lock-free algorithms. This makesflumeparticularly beneficial for highly concurrent programs, where the queue might need to handle a large number of messages in parallel, unlike the standard library channels that rely on a blocking mutex for synchronization.

Next, we need to import the following into our main.rs file:

usestd::{future::Future,panic::catch_unwind,thread};usestd::pin::Pin;usestd::task::{Context,Poll};usestd::time::Duration;usestd::sync::LazyLock;useasync_task::{Runnable,Task};usefutures_lite::future;

We will cover what we have imported when we use the imports in the code throughout the chapter so you understand their context.

Each of our three tasks needs to be able to be passed into the queue. We should start by building the task-spawning function. This is where we pass a future into the function. The function then converts the future into a task and puts the task on the queue to be executed. At this point, it might seem like a complex function, so let’s start with this signature:

fnspawn_task<F,T>(future:F)->Task<T>whereF:Future<Output=T>+Send+'static,T:Send+'static,{...}

This is a generic function that accepts any type that implements both the Future and Send traits. This makes sense because we do not want to be restricted to sending one type of future through our function. The Future trait denotes that our future is going to result in either an error or the value T. Our future needs the Send trait because we are going to be sending our future into a different thread where the queue is based. The Send trait enforces constraints that ensure that our future can be safely shared among threads.

The static means that our future does not contain any references that have a shorter lifetime than the static lifetime. Therefore, the future can be used for as long as the program is running. Ensuring this lifetime is essential, as we cannot force programmers to wait for a task to finish. If the developer never waits for a task, the task could run for the entire lifetime of the program. Because we cannot guarantee when a task is finished, we must ensure that the lifetime of our task is static. When browsing async code, you may have seen async move utilized. This is where we move the ownership of variables used in the async closure to the task so we can ensure that the lifetime is static.

Now that we have defined our spawn_task function signature, we move on to the first block of code in the function, which defines the task queue:

staticQUEUE:LazyLock<flume::Sender<Runnable>>=LazyLock::new(||{...});

With static we are ensuring that our queue is living throughout the lifetime of the program. This makes sense, as we will want to send tasks to our queue throughout the program’s lifetime. The LazyLock struct gets initialized on its first access. Once the struct is initialized, it is not initialized again. This is because we will be calling our task-spawning function every time we send a future to the async runtime. If we initialize the queue every time we call spawn_task, we would be wiping the queue of previous tasks. We now have the transmitting end of a channel, which sends Runnable.

Runnable is a handle for a runnable task. Every spawned task has a single Runnable handle, which exists only when the task is scheduled for running. The handle has the run function that polls the task’s future once. Then the runnable is dropped. The runnable appears again only when the waker wakes the task in turn, scheduling the task again. Recall from Chapter 2, if we do not pass the waker into our future, it will not be polled again. This is because the future cannot be woken to be polled again. We can build an async runtime that will poll futures no matter whether a waker is present, and we explore this in Chapter 10.

Now that we have defined our signature of the queue, we can look into the closure that we passed into LazyLock. We need to create our channel as well as a mechanism for receiving futures sent to that channel:

let(tx,rx)=flume::unbounded::<Runnable>();thread::spawn(move||{whileletOk(runnable)=rx.recv(){println!("runnable accepted");let_=catch_unwind(||runnable.run());}});tx

After we have created the channel, we spawn a thread that waits for incoming traffic. The waiting for the incoming traffic is blocking because we are building the async queues to handle incoming async tasks. As a result, we cannot rely on async in our thread. Once we have received our runnable, we run it in the catch_unwind function. We use this because we do not know the quality of the code being passed to our async runtime. Ideally, all Rust developers would handle possible errors properly, but in case they do not, catch_unwind runs the code and catches any error that’s thrown while the code is running, returning Ok or Err depending on the outcome. This is to prevent a badly coded future from blowing up our async runtime. We then return the transmitter channel so we can send runnables to our thread.

We now have a thread that is running and waiting for tasks to be sent to that thread to be processed, which we achieve with this code:

letschedule=|runnable|QUEUE.send(runnable).unwrap();let(runnable,task)=async_task::spawn(future,schedule);

Here, we have created a closure that accepts a runnable and sends it to our queue. We then create the runnable and task by using the async_task spawn function. This function leads to an unsafe function that allocates the future onto the heap. The task and runnable returned from the spawn function have a pointer to the same future.

Note

In this chapter, we will not be building our own executor or code that creates a runnable or schedules the task. We will do this in Chapter 10 as we build an async server completely from the standard library with no external dependencies.

Now that the runnable and task have pointers to the same future, we have to schedule the runnable to be run and return the task:

runnable.schedule();println!("Here is the queue count: {:?}",QUEUE.len());returntask

When we schedule the runnable, we essentially put the task on the queue to be processed. If we did not schedule the runnable, the task would not be run, and our program would crash when we try to block the main thread to wait on the task being executed (because there is no runnable on the queue but we still return the task). Remember, the task and the runnable have pointers to the same future.

Now that we have scheduled our runnable to be run on the queue and returned the task, our basic async runtime is complete. All we need to do is build some basic futures. We are going to have two types of tasks.

The first task type is our CounterFuture, which we initially explored in Chapter 2. This future increments a counter and prints the result after each poll, simulating a delay by using a std::thread::sleep call. Here is the code:

structCounterFuture{count:u32,}implFutureforCounterFuture{typeOutput=u32;fnpoll(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{self.count+=1;println!("polling with result: {}",self.count);std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));ifself.count<3{cx.waker().wake_by_ref();Poll::Pending}else{Poll::Ready(self.count)}}}

The second task (task 3) is an async function created using the async/await syntax. This function sleeps for 1 second before printing a message. Here’s the code:

asyncfnasync_fn(){std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));println!("async fn");}

In this example, we are not manually writing our own polling mechanism as we did with CounterFuture. Instead, we’re using the built-in async functionality provided by Rust’s async syntax, which automatically handles the polling and scheduling of the task for us. Note that our sleep in async_fn is blocking because we want to see how the tasks are processed in our queue.

Before we progress, we can take a detour to get an appreciation for how nonblocking async sleep functions work. Throughout this chapter, we are using sleep functions that block the executor. We are doing this for educational purposes so we can easily map how our tasks are processed in our runtime. However, if we want to build an efficient async sleep function, we need to lean into getting the executor to poll our sleep future and return Pending if the time has not elapsed. First we need Instant to calculate the time elapsed and two fields to keep track of the sleep:

usestd::time::Instant;structAsyncSleep{start_time:Instant,duration:Duration,}implAsyncSleep{fnnew(duration:Duration)->Self{Self{start_time:Instant::now(),duration,}}}

We can then check the time elapsed between now and start_time on every poll, returning Pending if the time elapsed it not sufficient:

implFutureforAsyncSleep{typeOutput=bool;fnpoll(self:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{letelapsed_time=self.start_time.elapsed();ifelapsed_time>=self.duration{Poll::Ready(true)}else{cx.waker().wake_by_ref();Poll::Pending}}}

This will not block the executor with idle sleep time. Because sleep is only one part of a process, we can call the await on our future inside async blocks for our async sleep future as follows:

letasync_sleep=AsyncSleep::new(Duration::from_secs(5));letasnyc_sleep_handle=spawn_task(async{async_sleep.await;...});

Note

Like most things in programming, a trade-off always exists. If a lot of tasks are in front of the sleep task, chances increase that the async sleep task might effectively wait longer than the duration required before finishing because it might have to wait for other tasks to complete before it can complete between every poll. If you have an operation requiring x seconds to pass between two steps, a blocking sleep might be a better option, but you are going to quickly clog up your queues if you have a lot of these tasks.

Going back to our blocking example, we can now run some futures in our runtime with the following main function:

fnmain(){letone=CounterFuture{count:0};lettwo=CounterFuture{count:0};lett_one=spawn_task(one);lett_two=spawn_task(two);lett_three=spawn_task(async{async_fn().await;async_fn().await;async_fn().await;async_fn().await;});std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(5));println!("before the block");future::block_on(t_one);future::block_on(t_two);future::block_on(t_three);}

This main function has some repetition, but it is needed in order for us to get a sense of how the async runtime we just built processes futures. Notice that task 3 consists of multiple calls to async_fn. This helps us see how the runtime handles multiple async operations within a single task. We then wait 5 seconds and print so we can get a sense of how our system runs before calling the block_on functions.

Running our program gives us the following lengthy but essential printout in the terminal:

Here is the queue count: 1 Here is the queue count: 2 Here is the queue count: 3 runnable accepted polling with result: 1 runnable accepted polling with result: 1 runnable accepted async fn async fn before the block async fn async fn runnable accepted polling with result: 2 runnable accepted polling with result: 2 runnable accepted polling with result: 3 runnable accepted polling with result: 3

Our printout gives us a timeline of our async runtime. We can see that our queue is being filled up with the three tasks that we have spawned, and our runtime is processing them in order asynchronously before we call our block_on functions. Even after the first block_on function is called, which blocks on the first task we spawned, the two counter tasks are being processed at the same time.

Note that the async function that we built and called four times in our third task was essentially blocking. There was no await within the async function, even though we use the await syntax like so:

async{async_fn().await;async_fn().await;async_fn().await;async_fn().await;}

The stack of async_fn futures blocks the thread that’s processing the task queue until the entire task is completed. When a poll results in Pending, the task is then put back on the queue to be polled again.

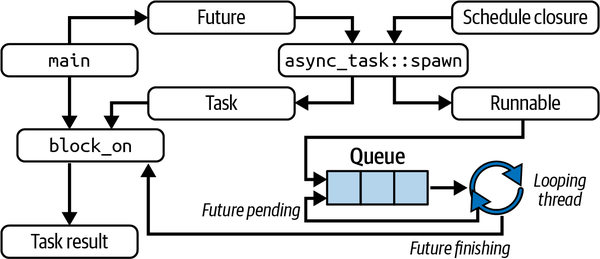

Our async runtime can be summarized by the diagram in Figure 3-1.

Figure 3-1. Our async runtime

Let’s describe what is happening with an analogy. Say that we have a dirty coat that needs cleaning. The label inside the coat that indicates cleaning instructions and material content is the future. We walk into the dry cleaners and hand over the coat with the instructions. The worker at the cleaner makes the coat runnable by putting a plastic cover on it and giving it a number. The worker also gives you a ticket with the number, which is like the task that the main function gets.

We then go about our day doing things while the coat is being cleaned. If the coat is not cleaned the first time around, it keeps going through cleaning cycles until it is clean. We then come back with our ticket and hand it over to the worker. This is the same stage as the block_on function. If we have really taken our time before coming back, the coat might be clean already and we can take it and go on with our day. If we go to the cleaners too early, the coat will not be clean, and we’ll have to wait until the coat is cleaned before taking it home. The clean coat is the result.

Right now, our async runtime has only one thread processing the queue. This would be like us insisting on only one worker at the cleaners. This is not the most efficient use of resources available, as most CPUs have multiple cores. Considering this, it would be useful to explore how to increase the number of workers and queues to increase our capacity to handle more tasks.

Increasing Workers and Queues

To increase our number of threads working on the queue, we can add another thread consuming from the queue with a cloned receiver of our queue channel:

let(tx,rx)=flume::unbounded::<Runnable>();letqueue_one=rx.clone();letqueue_two=rx.clone();thread::spawn(move||{whileletOk(runnable)=queue_one.recv(){let_=catch_unwind(||runnable.run());}});thread::spawn(move||{whileletOk(runnable)=queue_two.recv(){let_=catch_unwind(||runnable.run());}});

If we send tasks through the channel, the traffic will generally be distributed across both threads. If one thread is blocked with a CPU-intensive task, the other thread will continue to work through tasks. Recall that Chapter 1 proved that CPU-intensive tasks can be run in parallel by using threads with our Fibonacci number example. We can have a more ergonomic approach to building a thread pool with the following code:

for_in0..3{letreceiver=rx.clone();thread::spawn(move||{whileletOk(runnable)=receiver.recv(){let_=catch_unwind(||runnable.run());}});}

We could offload CPU-intensive tasks to our thread pool and continue working through the rest of the program, blocking it when we need a result from the task. While this is not really in the spirit of async programming (as we use async programming to optimize the juggling of I/O operations), it is a useful approach to remember that certain problems can be solved by off-loading CPU-intensive tasks early in the program.

Warning

You may have come across warnings along the lines of “async is not for computationally heavy tasks.” Async is merely a mechanism, and you can use it for what you want as long as it makes sense. However, the warning is not without merit. For instance, if you are using your async runtime to handle income requests as most web frameworks do, then chucking computationally heavy tasks onto the async runtime queue could potentially block your ability to process incoming requests until those computations are done.

Now that we have explored multiple workers, we should really look into multiple queues.

Passing Tasks to Different Queues

One of the reasons we would want to have multiple queues is that we might have different priorities for tasks. In this section, we are going to build a high-priority queue with two consuming threads and a low-priority queue with one consuming thread. To support multiple queues, we need the following enum to classify the type of queue the task is destined for:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy)]enumFutureType{High,Low}

We also need our futures to yield the future type when passed into our spawn function by utilizing the trait:

traitFutureOrderLabel:Future{fnget_order(&self)->FutureType;}

We then need to add the future type by adding an extra field:

structCounterFuture{count:u32,order:FutureType}

Our poll function stays the same, so we don’t need to revisit that. However, we do need to implement the FutureOrderLabel trait for our future:

implFutureOrderLabelforCounterFuture{fnget_order(&self)->FutureType{self.order}}

Our future is now ready to be processed, and we need to reformat our async runtime to use future types. The signature for our spawn_task function stays the same, apart from the additional trait:

fnspawn_task<F,T>(future:F)->Task<T>whereF:Future<Output=T>+Send+'static+FutureOrderLabel,T:Send+'static,{...}

We can now define our two queues. At this point, you can attempt to code them yourself before moving forward, as we have covered all that we need to build the two queues. If you attempted to build the queues, hopefully they take a form similar to the following:

staticHIGH_QUEUE:LazyLock<flume::Sender<Runnable>>=LazyLock::new(||{let(tx,rx)=flume::unbounded::<Runnable>();for_in0..2{letreceiver=rx.clone();thread::spawn(move||{whileletOk(runnable)=receiver.recv(){let_=catch_unwind(||runnable.run());}});}tx});staticLOW_QUEUE:LazyLock<flume::Sender<Runnable>>=LazyLock::new(||{let(tx,rx)=flume::unbounded::<Runnable>();for_in0..1{letreceiver=rx.clone();thread::spawn(move||{whileletOk(runnable)=receiver.recv(){let_=catch_unwind(||runnable.run());}});}tx});

The low-priority queue has one consuming thread, and the high-priority queue has two consuming threads. We now need to route futures to the correct queue. This can be done by defining an individual runner closure for each queue and then passing the correct closure based on the future type:

letschedule_high=|runnable|HIGH_QUEUE.send(runnable).unwrap();letschedule_low=|runnable|LOW_QUEUE.send(runnable).unwrap();letschedule=matchfuture.get_order(){FutureType::High=>schedule_high,FutureType::Low=>schedule_low};let(runnable,task)=async_task::spawn(future,schedule);runnable.schedule();returntask

We can now create a future that can be inserted into the selected queue:

letone=CounterFuture{count:0,order:FutureType::High};

However, we have a problem. Let’s imagine that loads of low-priority tasks get created, and there are no high-priority tasks. We would have one consumer thread working on all the tasks while the other two consumer threads are just sitting idle. We would be working at one-third capacity. This is where task stealing comes in.

Note

We do not need to write our own async runtime queues to have control over the distribution of tasks. For instance, Tokio will allow you to have control over the distribution of tasks by using LocalSet. We cover this in Chapter 7.

Task Stealing

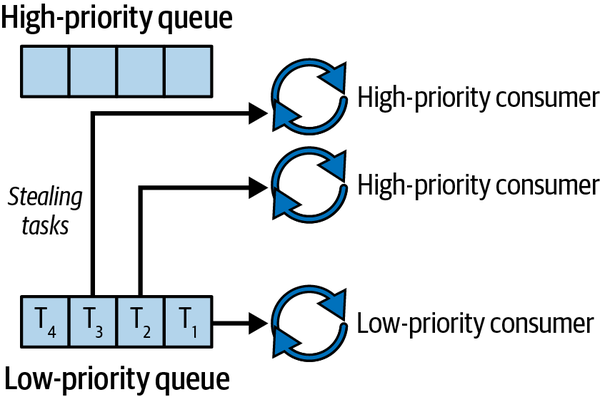

In task stealing, consuming threads steal tasks from other queues when their own queue is empty. Figure 3-2 shows task stealing in relation to our current async system.

Figure 3-2. Task stealing

We also must appreciate that stealing can go the other way. If the low-priority queue is empty, we would want the low-priority consumer thread to steal tasks from the high-priority queue.

To achieve task stealing, we need to pass in channels for the high- and low-priority queues into both queues. Before we can define our channels, we need this import:

useflume::{Sender,Receiver};

If we used the standard library for our Sender and Receiver, we would not be able to send the Sender or Receiver over to other threads. With flume, we make both of the channels static that are lazily evaluated inside our spawn_task function:

staticHIGH_CHANNEL:LazyLock<(Sender<Runnable>,Receiver<Runnable>)>=LazyLock::new(||flume::unbounded::<Runnable>());staticLOW_CHANNEL:LazyLock<(Sender<Runnable>,Receiver<Runnable>)>=LazyLock::new(||flume::unbounded::<Runnable>());

Now that we have our two channels, we need to define our high-priority queue consumer threads to carry out the following steps for each iteration in an infinite loop:

-

Check

HIGH_CHANNELfor a message. -

If

HIGH_CHANNELdoes not have a message, checkLOW_CHANNELfor a message. -

If

LOW_CHANNELdoes not have a message, wait for 100 ms for the next iteration.

Note

We could park our threads if they are idle and wake them when they need to process incoming tasks. This can save excessive looping and sleeping when there are no tasks to be processed. However, relying on sleeping in your threads can increase response latency, which is undesirable in production code. In production environments, you should aim to avoid sleeping in threads and instead use more responsive mechanisms like thread parking or condition variables. We cover thread parking in relation to async queues in Chapter 10.

Our high-priority queue can carry out these steps with the following code:

staticHIGH_QUEUE:LazyLock<flume::Sender<Runnable>>=LazyLock::new(||{for_in0..2{lethigh_receiver=HIGH_CHANNEL.1.clone();letlow_receiver=LOW_CHANNEL.1.clone();thread::spawn(move||{loop{matchhigh_receiver.try_recv(){Ok(runnable)=>{let_=catch_unwind(||runnable.run());},Err(_)=>{matchlow_receiver.try_recv(){Ok(runnable)=>{let_=catch_unwind(||runnable.run());},Err(_)=>{thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(100));}}}};}});}HIGH_CHANNEL.0.clone()});

Our low-priority queue would merely swap steps 1 and 2 around and return LOW_CHANNEL.0.clone. We now have both queues pulling tasks from their own queues first and then pulling tasks from other queues when there are no tasks on their own queue. When no tasks are left, we then have our consumer threads slow down.

Warning

Remember that the queues and channels are lazy in their evaluation. A task needs to be sent to the queue in order for the queue to start running. If you send tasks to only the low-priority queue and never to the high-priority queue, the high-priority queue will never start up and therefore will never steal tasks from the low-priority queue.

At this milestone, we can sit back and think about what we have done. We have created our own async runtime queue and defined different queues! We now have fine-grained control over how our async tasks run. Note that we may not want task stealing. For instance, if we put CPU-intensive tasks onto the high-priority queue and lightweight networking tasks on the low-priority queue, we would not want the low-priority queue stealing tasks from the high-priority queue. Otherwise, we run the risk of shutting down our network processing because of the low-priority-queue consumer threads being held up on CPU-intensive tasks.

While it was interesting to have the trait constraint and see how it could be implemented onto our future, we are now disadvantaged. We cannot pass in simple async blocks or async functions because they do not have the FutureOrderLabel trait implemented. Other developers will just want a nice interface to run their tasks. Could you imagine how bloated our code would be if we had to implement the Future trait for every async task and implement the FutureOrderLabel on all of them? We need to refactor our spawn_task function for a better developer experience.

Refactoring Our spawn_task Function

When it comes to allowing async blocks and async functions into our spawn_task function, we need to remove the FutureOrderLabel trait and remove our order field in our CounterFuture struct. We then must remove the constraint of the FutureOrderLabel trait in our spawn_task function and add another argument for the order, giving the following function signature:

fnspawn_task<F,T>(future:F,order:FutureType)->Task<T>whereF:Future<Output=T>+Send+'static,T:Send+'static,{

We also need to update the selection of the correct scheduling closure in the spawn_task function:

letschedule=matchorder{FutureType::High=>schedule_high,FutureType::Low=>schedule_low};

Still, we do not want our developers stressing over the order, so we can create a macro for the spawn_task function:

macro_rules!spawn_task{($future:expr)=>{spawn_task!($future,FutureType::Low)};($future:expr,$order:expr)=>{spawn_task($future,$order)};}

This macro allows us to pass in just the future. If we pass in only the future, we then pass in the low-priority type, meaning that this is the default type. If the order is passed in, it is passed into the spawn_task function. From this macro, Rust works out that you need to at least pass in the future expression, and it will not compile unless the future is supplied. We now have a more ergonomic way of spawning tasks, as you can see with the following example:

fnmain(){letone=CounterFuture{count:0};lettwo=CounterFuture{count:0};lett_one=spawn_task!(one,FutureType::High);lett_two=spawn_task!(two);lett_three=spawn_task!(async_fn());lett_four=spawn_task!(async{async_fn().await;async_fn().await;},FutureType::High);future::block_on(t_one);future::block_on(t_two);future::block_on(t_three);future::block_on(t_four);}

This macro is flexible. A developer using it could casually spawn tasks without thinking about it but also has the ability to state that the task is a high priority if needed. We can also pass in async blocks and async functions because these are just syntactic sugar for futures. However, we are repeating ourselves when blocking the main function to wait on multiple tasks. We need to create our own join macro to prevent this repetition.

Creating Our Own Join Macro

To create our own join macro, we need to accept a range of tasks and call the block_on function. We can define our own join macro with the following code:

macro_rules!join{($($future:expr),*)=>{{letmutresults=Vec::new();$(results.push(future::block_on($future));)*results}};}

It is essential that we keep the order of the results the same as the order of the futures passed in. Otherwise, the user will have no way of knowing which result belongs to which task. Also note that our join macro will return only one type, so we use our join macro as follows:

letoutcome:Vec<u32>=join!(t_one,t_two);letoutcome_two:Vec<()>=join!(t_four,t_three);

The outcome is a vector of the outputs of the counters, and outcome_two is a vector of the outputs for the async functions that didn’t return anything. As long as we have the same return type, this code will work.

We must remember that our tasks are being directly run. An error could occur in the execution of the task. To return a vector of results, we can create a try_join macro with this code:

macro_rules!try_join{($($future:expr),*)=>{{letmutresults=Vec::new();$(letresult=catch_unwind(||future::block_on($future));results.push(result);)*results}};}

This is similar to our join! macro but will return results of the tasks.

We now have nearly everything we need to run async tasks on our runtime in an ergonomic way with task stealing and different queues. Though spawning our tasks is not ergonomic, we still need a nice interface to configure our runtime environment.

Configuring Our Runtime

You may remember that the queue is lazy: it will not start until it is called. This directly affects our task stealing. The example we gave was that if no tasks were sent to the high-priority queue, that queue would not start and therefore would not steal tasks from the low-priority queue if empty, and vice versa. Configuring a runtime to get things going and refine the number of consuming loops is not an unusual way of solving this problem. For instance, we can look at the following Tokio example of starting its runtime:

usetokio::runtime::Runtime;// Create the runtimeletrt=Runtime::new().unwrap();// Spawn a future onto the runtimert.spawn(async{println!("now running on a worker thread");});

At the time of this writing, the preceding example is in the Tokio documentation of the runtime struct. The Tokio library also uses procedural macros to set up the runtime, but they are beyond the scope of this book. You can find more information on procedural macros in the Rust documentation. For our runtime, we can build a basic runtime builder to define the number of consuming loops on the high- and low-priority queues.

We first start with our runtime struct:

structRuntime{high_num:usize,low_num:usize,}

The high number is the number of consuming threads for the high-priority queue, and the low number is the number of consuming threads for the low-priority queue. We implement the following functions for our runtime:

implRuntime{pubfnnew()->Self{letnum_cores=std::thread::available_parallelism().unwrap().get();Self{high_num:num_cores-2,low_num:1,}}pubfnwith_high_num(mutself,num:usize)->Self{self.high_num=num;self}pubfnwith_low_num(mutself,num:usize)->Self{self.low_num=num;self}pubfnrun(&self){...}}

Here we have a standard way of defining the numbers based on the number of available cores on the computer running our async program. We then have the option to define the low and high numbers ourselves if we want. Our run function defines the environment variables for the numbers and then spawns two tasks to both queues to set up the queues:

pubfnrun(&self){std::env::set_var("HIGH_NUM",self.high_num.to_string());std::env::set_var("LOW_NUM",self.low_num.to_string());lethigh=spawn_task!(async{},FutureType::High);letlow=spawn_task!(async{},FutureType::Low);join!(high,low);}

We use our join so that after the run function has been executed, both of our queues are ready to steal tasks.

Before we try our runtime, we need to use these environment variables to establish the number of consumer threads for each queue. In our spawn_task function, we refer to the environment variable inside each queue definition:

staticHIGH_QUEUE:LazyLock<flume::Sender<Runnable>>=LazyLock::new(||{lethigh_num=std::env::var("HIGH_NUM").unwrap().parse::<usize>().unwrap();for_in0..high_num{...

The same goes for the low queue. We can then define our runtime with default numbers in our main function before anything else:

Runtime::new().run();

Or we can use custom numbers with the following:

Runtime::new().with_low_num(2).with_high_num(4).run();

We are now capable of running our spawn_task function and join macro whenever we want throughout the rest of the program. We have our own runtime that is configurable with two types of queues and task stealing!

We now have nearly everything tied up. However, we need to cover one last concept before finishing the chapter: background processes.

Running Background Processes

Background processes are tasks that execute in the background periodically for the entire lifetime of the program. These processes can be used for monitoring and for maintenance tasks such as database cleanup, log rotation, and data updates to ensure that the program always has access to the latest information. Implementing a basic background process as a task in the async runtime will illustrate how to handle our long-running tasks.

Before we handle the background task, we need to create a future that will never stop being polled. At this stage in the chapter, you should be able to build this yourself, and you should attempt to do this before moving on.

If you have attempted to build your own future, it should take the following form if the process being carried out is blocking:

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Copy)]structBackgroundProcess;implFutureforBackgroundProcess{typeOutput=();fnpoll(self:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{println!("background process firing");std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));cx.waker().wake_by_ref();Poll::Pending}}

Your implementation might be different, but the key takeaway is that we are always returning Pending.

We need to acknowledge here that if we drop a task in our main function, the task being executed in the async runtime will be cancelled and will not be executed, so our background task must be present throughout the entire lifetime of the program. We need to send the background task at the very beginning of main, right after we have defined our runtime:

Runtime::new().with_low_num(2).with_high_num(4).run();let_background=spawn_task!(BackgroundProcess{});

And our background process will run periodically throughout the entire lifetime of our program.

However, this is not ergonomic. For instance, let’s say that a struct or function could create a background-running task. We do not need to try to juggle the task around the program so it does not get dropped, cancelling the background task. We can remove the need for juggling tasks to keep the background task running by using the detach method:

Runtime::new().with_low_num(2).with_high_num(4).run();spawn_task!(BackgroundProcess{}).detach();

This method moves the pointer in the task into an unsafe loop that will poll the task and schedule it until it is finished. The pointer associated with the task in the main function is then dropped, dropping the need for keeping hold of the tasks in main.

Summary

In this chapter, we implemented our own runtime, and you learned a lot in the process. We initially built a basic async runtime environment that accepted futures and created tasks and runnables. The runnables were put on the queue to be processed by consumer threads, and the task was returned back to the main function, which we can block to wait for the result of the task. Here we spent some time solidifying the steps that the futures and tasks go through in the async runtime. Finally, we implemented queues with different numbers of consuming threads and used this pattern to implement task stealing for situations when a queue is empty. We then created our own macros for users so they could easily spawn tasks and join them.

The nuance that task stealing introduces highlights the true nature of async programming. An async runtime is merely a tool that you use to solve your problems. Nothing is stopping you from having one thread on a queue for accepting network traffic and five threads processing long, CPU-intensive tasks if you have a program with little traffic but that traffic requests the triggering of long-running tasks. In this case, you would not want your network queue to steal from the CPU-intensive queue. Of course, your solutions should strive to be sensible. However, with deeper understanding of the async runtime you’re using comes the ability to solve complex problems in interesting ways.

The async runtime we built certainly is not the best out there. Established async runtimes have teams of very smart people ironing out problems and edge cases. However, now that you are at the end of this chapter, you should understand the need to read around the specifics of your chosen runtime so you can apply its attributes to your own set of problems that you’re trying to solve. Also note that the simple implementation of the async_task queue with the flume channel can be used in production.

In Chapter 4, we cover integrating HTTP with our own async runtime.