Chapter 2. Basic Async Rust

This chapter introduces the important components of using async in Rust and gives an overview of tasks, futures, async, and await. We cover context, pins, polling, and closures—important concepts for fully taking advantage of async programming in Rust. We have chosen the examples in this chapter to demonstrate the learning points; they may not necessarily be optimal for efficiency. The chapter concludes with an example of building an async audit logger for a sensitive program, pulling all the concepts together.

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to define a task and a future. You’ll also understand the more technical components of a future, including context and pins.

Understanding Tasks

In asynchronous programming, a task represents an asynchronous operation. The task-based asynchronous pattern (TAP) provides an abstraction over asynchronous code. You write code as a sequence of statements. You can read that code as though each statement completes before the next begins. For instance, let’s think about making a cup of coffee and toast, which requires the following steps:

-

Put bread in toaster

-

Butter toasted bread

-

Boil water in kettle

-

Pour milk

-

Put in instant coffee granules (not the best, but simplifies the example)

-

Pour boiled water

We can definitely apply async programming to speed this up, but first we need to break down all the steps into two big steps, make coffee and make toast, as follows:

-

Make coffee

-

Boil water in kettle

-

Pour milk

-

Put in instant coffee

-

Pour boiled water

-

-

Make toast

-

Put bread in toaster

-

Butter toasted bread

-

Even though each of us has only one pair of hands, we can run these two steps at the same time. We can boil the water, and while the water is boiling, we can put the bread in the toaster. We have a bit of dead time while we wait for the kettle and toaster, so if we wanted to be more efficient and we were comfortable with the risk that we could end up pouring the boiled water before adding the coffee and milk due to an instant boil, we could break the steps down even more as follows:

-

Prep coffee mug

-

Pour milk

-

Put in instant coffee

-

-

Make coffee

-

Boil water in kettle

-

Pour boiled water

-

-

Make toast

-

Put bread in toaster

-

Butter toasted bread

-

While waiting for the boiling of the water and toasting of the bread, we can execute the pouring of the milk and adding the coffee, reducing the dead time. First of all, we can see that steps are not goal specific. When we walk into the kitchen, we will think make toast and make coffee, which are two separate goals. But we have defined three steps for those two goals. Steps are about what you can run at the same time out of sync to achieve all your goals.

Note that a trade-off arises when it comes to assumptions and what we are willing to tolerate. For instance, it may be completely unacceptable to pour boiling water before adding milk and coffee. This is a risk if there is no delay in the boiling of the kettle. However, we can make the safe assumption that there will be a delay.

Now that you understand what steps are, we can turn back to our example by using a high-level crate like Tokio that enables us to focus on the concepts of steps and how they relate to tasks. Don’t worry—we will use other crates in later chapters when we delve into lower-level concepts. First, we need to import the following:

usestd::time::Duration;usetokio::time::sleep;usestd::thread;usestd::time::Instant;

We use the Tokio sleep for steps that we can wait on, such as the boiling of the kettle and the toasting of the bread. Because the Tokio sleep function is nonblocking, we can switch to another step when the water is boiling or the bread is toasting. We use thread::sleep to simulate a step that we use both our hands for, as we can’t do anything else while pouring milk/water or buttering toast. In general, programming these steps will be CPU intensive. We can then define our prepping of the mug step with the following code:

asyncfnprep_coffee_mug(){println!("Pouring milk...");thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(3));println!("Milk poured.");println!("Putting instant coffee...");thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(3));println!("Instant coffee put.");}

We then define the “make coffee” step:

asyncfnmake_coffee(){println!("boiling kettle...");sleep(Duration::from_secs(10)).await;println!("kettle boiled.");println!("pouring boiled water...");thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(3));println!("boiled water poured.");}

And we define our last step:

asyncfnmake_toast(){println!("putting bread in toaster...");sleep(Duration::from_secs(10)).await;println!("bread toasted.");println!("buttering toasted bread...");thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(5));println!("toasted bread buttered.");}

You may have noticed that await is used on the Tokio sleep functions that represent the steps that are not intensive and that we can wait on. We use the await keyword to suspend the execution of our step until the result is ready. When the await is hit, the async runtime can switch to another async task.

Note

You can read more about async and await syntaxes on the Rust RFC book website.

Now that we have all our steps defined, we can run them in asynchronously with this code:

#[tokio::main]asyncfnmain(){letstart_time=Instant::now();letcoffee_mug_step=prep_coffee_mug();letcoffee_step=make_coffee();lettoast_step=make_toast();tokio::join!(coffee_mug_step,coffee_step,toast_step);letelapsed_time=start_time.elapsed();println!("It took: {} seconds",elapsed_time.as_secs());}

Here, we define our steps, which are called futures. We will cover futures in the next section. For now, think of futures as placeholders for something that may or may not have completed yet. We then wait for our steps to complete and then print out the time taken. If we run our program, we get the following:

Pouring milk... Milk poured. Putting instant coffee... Instant coffee put. boiling kettle... putting bread in toaster... kettle boiled. pouring boiled water... boiled water poured. bread toasted. buttering toasted bread... toasted bread buttered. It took: 24 seconds

This printout is a bit lengthy, but it is important. We can see that it looks strange. If we are being efficient, we would not start pouring milk and adding coffee. Instead, we would get the kettle boiling and put the bread in the toaster, and then go to pour milk. We can see that preparing the mug was first passed into the tokio::join macro. If we run our program again and again, the preparation of the mug will always be the first future to be executed.

Now, if we go back to the mug preparation function, we simply add a nonblocking sleep function before the rest of the processes:

asyncfnprep_coffee_mug(){sleep(Duration::from_millis(100)).await;...}

This gives us the following printout:

boiling kettle... putting bread in toaster... Pouring milk... Milk poured. Putting instant coffee... Instant coffee put. bread toasted. buttering toasted bread... toasted bread buttered. kettle boiled. pouring boiled water... boiled water poured. It took: 18 seconds

OK, now the order makes sense: we are boiling the water, putting bread in the toaster, and then pouring milk, and as a result, we saved 6 seconds. However, the cause and effect is counterintuitive. Putting in an extra sleep function has reduced our overall time. This is because that extra sleep function allowed the async runtime to switch context to other tasks and execute them until their await line was executed, and so on. This insertion of an artificial delay in the future to get the call rolling on other futures is informally referred to as cooperative multitasking.

When we pass our futures into the tokio::join macro, all the async expressions are evaluated concurrently in the same task. The join macro does not create tasks; it merely enables multiple futures to be executed concurrently within the task. For instance, we can spawn a task with the following code:

letperson_one=tokio::task::spawn(async{prep_coffee_mug().await;make_coffee().await;make_toast().await;});

Each future in the task will block further execution of that task until the future is finished. So, say we use the following annotation to ensure that the runtime has one worker:

#[tokio::main(flavor ="multi_thread", worker_threads = 1)]

We create two tasks, each representing a person, which will result in a 36-second runtime:

letperson_one=tokio::task::spawn(async{letcoffee_mug_step=prep_coffee_mug();letcoffee_step=make_coffee();lettoast_step=make_toast();tokio::join!(coffee_mug_step,coffee_step,toast_step);}).await;letperson_two=tokio::task::spawn(async{letcoffee_mug_step=prep_coffee_mug();letcoffee_step=make_coffee();lettoast_step=make_toast();tokio::join!(coffee_mug_step,coffee_step,toast_step);}).await;

We can redefine the task with a join as opposed to blocking futures:

letperson_one=tokio::task::spawn(async{letcoffee_mug_step=prep_coffee_mug();letcoffee_step=make_coffee();lettoast_step=make_toast();tokio::join!(coffee_mug_step,coffee_step,toast_step);});letperson_two=tokio::task::spawn(async{letcoffee_mug_step=prep_coffee_mug();letcoffee_step=make_coffee();lettoast_step=make_toast();tokio::join!(coffee_mug_step,coffee_step,toast_step);});let_=tokio::join!(person_one,person_two);

Joining on two tasks representing people will result in a 28-second runtime. Join three tasks representing people would result in a 42-second runtime. Seeing as the total blocking time for each task is 14 seconds, the time increase makes sense. We can deduce from the linear increase in time that although three tasks are sent to the async runtime and put on the queue, the executor is setting the task to idle when coming across an await and working on the next task in the queue while polling the idle tasks.

Async runtimes can have multiple workers and queues, and we will explore writing our own runtime in Chapter 3. Considering what we have covered in this section, we can give the following definition of a task:

A task is an asynchronous computation or operation that is managed and driven by an executor to completion. It represents the execution of a future, and it may involve multiple futures being composed or chained together.

Futures

One of the key features of async programming is the concept of a future. We’ve mentioned that a future is a placeholder object that represents the result of an asynchronous operation that has not yet completed. Futures allow you to start a task and continue with other operations while the task is being executed in the background.

To truly understand how a future works, we’ll cover its lifecycle. When a future is created, it is idle. It has yet to be executed. Once the future is executed, it can either yield a value, resolve, or go to sleep because the future is pending (awaiting on a result). When the future is polled again, the poll can return either a Pending or Ready result. The future will continue to be polled until it is either resolved or cancelled.

To illustrate how futures work, let’s build a basic counter future. It will count up to 5 and then will be ready. First, we need to import the following:

usestd::future::Future;usestd::pin::Pin;usestd::task::{Context,Poll};usestd::time::Duration;usetokio::task::JoinHandle;

You should be able to understand most of this code. We will cover Context and Pin after building our basic future. Because our future is a counter, the struct takes the following form:

structCounterFuture{count:u32,}

We then implement the future trait:

implFutureforCounterFuture{typeOutput=u32;fnpoll(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{self.count+=1;println!("polling with result: {}",self.count);std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));ifself.count<5{cx.waker().wake_by_ref();Poll::Pending}else{Poll::Ready(self.count)}}}

Let’s not focus on Pin or Context just yet, but on the poll function as a whole. Every time the future is polled, the count is increased by one. If the count is at three, we then state that the future is ready. We introduce the std::thread::sleep function to merely exaggerate the time taken so it is easier to follow this example when running the code. To run our future, we simply need the following code:

#[tokio::main]asyncfnmain(){letcounter_one=CounterFuture{count:0};letcounter_two=CounterFuture{count:0};lethandle_one:JoinHandle<u32>=tokio::task::spawn(asyncmove{counter_one.await});lethandle_two:JoinHandle<u32>=tokio::task::spawn(asyncmove{counter_two.await});tokio::join!(handle_one,handle_two);}

Running two of our futures in different tasks gives us the following printout:

polling with result: 1 polling with result: 1 polling with result: 2 polling with result: 2 polling with result: 3 polling with result: 3 polling with result: 4 polling with result: 4 polling with result: 5 polling with result: 5

One of the futures was taken off the queue, polled, and set to idle, while another future was taken off the task queue to be polled. These futures were polled in alternate fashion. You may have noticed that our poll function is not async. This is because an async poll function would return a circular dependency, as you would be sending a future to be polled in order to resolve a future being polled. With this, we can see that the future is the bedrock of the async computation.

The poll function takes a mutable reference of itself. However, this mutable reference is wrapped in a Pin, which we need to discuss.

Pinning in Futures

In Rust, the compiler often moves values around in memory. For instance, if we move a variable into a function, the memory may be moved.

It’s not just moving values that may result in moving memory addresses. Collections can also change memory addresses. For instance, if a vector gets to capacity, the vector will have to be reallocated in memory, changing the memory address.

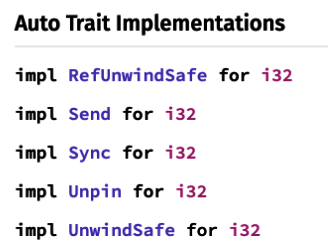

Most normal primitives such as number, string, bool, structs, and enum implement the Unpin trait, enabling them to be moved around. If you are unsure of whether your data type implements the Unpin trait, run a doc command and check the traits your data type implements. For example, Figure 2-1 shows the auto-trait implementations on an i32 in the standard docs.

Figure 2-1. Auto-trait implementations in documentation showing thread safety of a struct or primitive

So why do we concern ourselves with pinning and unpinning? We know that futures get moved, as we use async move in our code when spawning a task. However, moving can be dangerous. To demonstrate the data, we can build a basic struct that references itself:

usestd::ptr;structSelfReferential{data:String,self_pointer:*constString,}

The *const String is a raw pointer to a string. This pointer directly references the memory address of the data. The pointer offers no safety guarantees. Therefore, the reference does not update if the data being pointed to moves. We are using a raw pointer to demonstrate why pinning is needed. For this demonstration to take place, we need to define the constructor of the struct and printing of the struct’s reference, as follows:

implSelfReferential{fnnew(data:String)->SelfReferential{letmutsr=SelfReferential{data,self_pointer:ptr::null(),};sr.self_pointer=&sr.dataas*constString;sr}fn(&self){unsafe{println!("{}",*self.self_pointer);}}}

To then expose the danger of moving the struct by creating two instances of the SelfReferential struct, swap these instances in memory and print what data the raw pointer is pointing to with the following code:

fnmain(){letfirst=SelfReferential::new("first".to_string());letmoved_first=first;// Move the structmoved_first.();}

If you try to run the code, you will get an error, which is likely a segmentation fault. A segmentation fault is an error caused by accessing memory that does not belong to the program. We can see that moving a struct with a reference to itself can be dangerous. Pinning ensures that the future remains at a fixed memory address. This is important because futures can be paused or resumed, which can change the memory address.

We have covered nearly all the components in the basic future that we have defined. The only remaining component is the context.

Context in Futures

A Context only serves to provide access to a waker to wake a task. A waker is a handle that notifies the executor when the task is ready to be run.

While this is the primary role of Context today, it’s important to note that this functionality might evolve in the future. The design of Context has allowed space for expansion, such as the introduction of additional responsibilities or capabilities as Rust’s asynchronous ecosystem grows.

Let’s look at a stripped-down version of our poll function so we can focus on the path of waking up the future:

fnpoll(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{...ifself.count<5{cx.waker().wake_by_ref();Poll::Pending}else{Poll::Ready(self.count)}}

The waker is wrapped in the context and is only used when the result of the poll is going to be Pending. The waker is essentially waking up the future so it can be executed. If the future is completed, then no more execution needs to be done. If we were to remove the waker and run our program again, we would get the following printout:

polling with result: 1 polling with result: 1

Our program does not complete, and the program hangs. This is because our tasks are still idle, but there is no way to wake them up again to be polled and executed to completion. Futures need the Waker::wake() function so it can be called when the future should be polled again. The process takes the following steps:

-

The

pollfunction for a future is called, and the result is that the future needs to wait for an async operation to complete before the future is able to return a value. -

The future registers its interest in being notified of the operation’s completion by calling a method that references the waker.

-

The executor takes note of the interest in the future’s operation and stores the waker in a queue.

-

At some later time, the operation completes, and the executor is notified. The executor retrieves the wakers from the queue and calls

wake_by_refon each one, waking up the futures. -

The

wake_by_reffunction signals the associated task that should be scheduled for execution. The way this is done can vary depending on the runtime. -

When the future is executed, the executor will call the poll method of the future again, and the future will determine whether the operation has completed, returning a value if completion is achieved.

We can see that futures are used with an async/await function, but let’s think about how else they can be used. We can also use a timeout on a thread of execution: the thread finishes when a certain amount of time has elapsed, so we do not end up with a program that hangs indefinitely. This is useful when we have a function that can be slow to complete and we want to move on or error early. Remember that threads provide the underlying functionality for executing tasks. We import timeout from tokio::time and set up a slow task. In this case, we put this as a sleep for 10 seconds to exaggerate the effect:

usestd::time::Duration;usetokio::time::timeout;asyncfnslow_task()->&'staticstr{tokio::time::sleep(Duration::from_secs(10)).await;"Slow Task Completed"}

Now we set up our timeout—in this case, setting it to 3 seconds. The thread will end if the future is not completed within these 3 seconds. We match the result and print Task timed out:

#[tokio::main]asyncfnmain(){letduration=Duration::from_secs(3);letresult=timeout(duration,slow_task()).await;matchresult{Ok(value)=>println!("Task completed successfully: {}",value),Err(_)=>println!("Task timed out"),}}

For CPU-intensive work, we can also offload work to a separate threadpool and the future resolves when the work is finished. We have now covered the context of futures.

Polling directly is not the most efficient way as our executor will be busy polling futures that are not ready. To explain how we can prevent busy polling, we will move onto waking futures remotely.

Waking Futures Remotely

Imagine that we make a network call to another computer using async Rust. The routing of the network call and receiving of the response happens outside of our Rust program. Considering this, it does not make sense to constantly poll our networking future until we get a signal from the OS that data has been received at the port we are listening to. We can hold on the polling of the future by externally referencing the future’s waker and waking the future when we need to.

To see this in action, we can simulate an external call with channels. First, we need the following imports:

usestd::pin::Pin;usestd::task::{Context,Poll,Waker};usestd::sync::{Arc,Mutex};usestd::future::Future;usetokio::sync::mpsc;usetokio::task;

With these imports, we can now define our future, which takes the following form:

structMyFuture{state:Arc<Mutex<MyFutureState>>,}structMyFutureState{data:Option<Vec<u8>>,waker:Option<Waker>,}

Here, we can see that the state of our MyFuture can be accessed from another thread. The state of our MyFuture has the waker and data. To make our main function more concise, we define a constructor for MyFuture with the following code:

implMyFuture{fnnew()->(Self,Arc<Mutex<MyFutureState>>){letstate=Arc::new(Mutex::new(MyFutureState{data:None,waker:None,}));(MyFuture{state:state.clone(),},state,)}}

For our constructor, we can see that we construct the future, but we also return a reference to the state so we can access the waker outside of the future. Finally, we implement the Future trait for our future with the following code:

implFutureforMyFuture{typeOutput=String;fnpoll(self:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{println!("Polling the future");letmutstate=self.state.lock().unwrap();ifstate.data.is_some(){letdata=state.data.take().unwrap();Poll::Ready(String::from_utf8(data).unwrap())}else{state.waker=Some(cx.waker().clone());Poll::Pending}}}

Here we can see that we print every time we poll the future to keep track of how many times we poll our future. We then access the state and see if there is any data. If there is no data, we pass the waker into the state so we can wake the future from outside of the future. If there is data in the state, we know that we are ready, and we return a Ready.

Our future is now ready to test. Inside our main function, we create our future, channel for communication, and spawn our future with the following code:

let(my_future,state)=MyFuture::new();let(tx,mutrx)=mpsc::channel::<()>(1);lettask_handle=task::spawn(async{my_future.await});tokio::time::sleep(tokio::time::Duration::from_secs(3)).await;println!("spawning trigger task");

We can see that we are sleeping for three seconds. This sleep gives us time to check if we are polling multiple times. If our approach works as intended, we should only get one poll during the time of sleeping. We then spawn our trigger task with the following code:

lettrigger_task=task::spawn(asyncmove{rx.recv().await;letmutstate=state.lock().unwrap();state.data=Some(b"Hello from the outside".to_vec());loop{ifletSome(waker)=state.waker.take(){waker.wake();break;}}});tx.send(()).await.unwrap();

We can see that once our trigger task recieves the message in the channel, it gets the state of our future, and populates the data. We then check to see if the waker is present. Once we get hold of the waker, we wake the future.

Finally, we await on both of the async tasks with the following code:

letoutome=task_handle.await.unwrap();println!("Task completed with outcome: {}",outome);trigger_task.await.unwrap();

If we run our code, we get this printout:

Polling the future spawning trigger task Polling the future Task completed with outcome: Hello from the outside

We can see that our polling only happens once on the initial setup and then happens one more time when we wake the future with the data. Async runtimes set up efficient ways to listen to OS events so they do not have to blindly poll futures. For instance, Tokio has an event loop that listens to OS events and then handles them so the event wakes up the right task. However, throughout this book, we want to keep the coding examples simple, so we will be calling the waker directly in the poll function. This is because we want to reduce the amount of superfluous code when focusing on other areas of async programming.

Now that we have covered how futures are woken from outside events, we now move onto sharing data between futures.

Sharing Data Between Futures

Although it can complicate things, we can share data between futures. We may want to share data between futures for the following reasons:

-

Aggregating results

-

Dependent computations

-

Caching results

-

Synchronization

-

Shared state

-

Task coordination and supervision

-

Resource management

-

Error propagation

While sharing data between futures is useful, there are some things that we need to be mindful of when doing so. We can highlight them as we work through a simple example. First, we will be relying on the standard Mutex with the following import:

usestd::sync::{Arc,Mutex};usetokio::task::JoinHandle;usecore::task::Poll;usetokio::time::Duration;usestd::task::Context;usestd::pin::Pin;usestd::future::Future;

We are using the standard Mutex rather than the Tokio version because we do not want async functionality in our poll function.

For our example, we will be using a basic struct that has a counter. One async task will be for increasing the count, and the other task will be decreasing the count. If both tasks hit the shared data the same number of times, the end result will be zero. Therefore, we need to build a basic enum to define what type of task is being run with the following code:

#[derive(Debug)]enumCounterType{Increment,Decrement}

We can then define our shared data struct with the following code:

structSharedData{counter:i32,}implSharedData{fnincrement(&mutself){self.counter+=1;}fndecrement(&mutself){self.counter-=1;}}

Now that our shared data struct is defined, we can define our counter future with the following code:

structCounterFuture{counter_type:CounterType,data_reference:Arc<Mutex<SharedData>>,count:u32}

Here, we have defined the type of operation the future will perform on the shared data. We also have access to the shared data and a count to stop the future once the total number of executions of the shared data has happened for the future.

The signature of our poll function takes the following form:

implFutureforCounterFuture{typeOutput=u32;fnpoll(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{...}}

Inside our poll function, we first cover getting access to the shared data with the following code:

std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));letmutguard=matchself.data_reference.try_lock(){Ok(guard)=>guard,Err(error)=>{println!("error for {:?}: {}",self.counter_type,error);cx.waker().wake_by_ref();returnPoll::Pending}};

We sleep to merely exaggerate the difference so it is easier for us to follow the flow of our program when running it. We then use a try_lock. This is because we are using the standard library Mutex. It would be nice to use the Tokio version of the Mutex, but remember that our poll function cannot be async. Here lies a problem. If we acquire the Mutex using the standard lock function, we can block the thread until the lock is acquired. Remember, we could have one thread handling multiple tasks in our runtime. We would defeat the purpose of the async runtime if we locked the entire thread until the Mutex is acquired. Instead, the try_lock function attempts to acquire the lock, returning a result immediately in whether the lock was acquired or not. If the lock is not acquired, we print out the error to inform us for educational purposes and then return a poll pending. This means that the future will be polled periodically until the lock is acquired so the future does not hold up the async runtime unnecessarily.

If we do get the lock, we then move forward in our poll function to act on the shared data with the following code:

letvalue=&mut*guard;matchself.counter_type{CounterType::Increment=>{value.increment();println!("after increment: {}",value.counter);},CounterType::Decrement=>{value.decrement();println!("after decrement: {}",value.counter);}}

Now that the shared data has been altered, we can return the right response depending on the count with the following code:

std::mem::drop(guard);self.count+=1;ifself.count<3{cx.waker().wake_by_ref();returnPoll::Pending}else{returnPoll::Ready(self.count)}

We can see that we drop the guard before bothering to work out the return. This increases the time the guard is free for other futures and enables us to update the self.count.

Running two different variants of our future can be done with the following code:

#[tokio::main]asyncfnmain(){letshared_data=Arc::new(Mutex::new(SharedData{counter:0}));letcounter_one=CounterFuture{counter_type:CounterType::Increment,data_reference:shared_data.clone(),count:0};letcounter_two=CounterFuture{counter_type:CounterType::Decrement,data_reference:shared_data.clone(),count:0};lethandle_one:JoinHandle<u32>=tokio::task::spawn(asyncmove{counter_one.await});lethandle_two:JoinHandle<u32>=tokio::task::spawn(asyncmove{counter_two.await});tokio::join!(handle_one,handle_two);}

Now we had to run the program a couple of times before we got an error that was printed out, but when an error acquiring the lock occurred, we got the following printout:

after decrement: -1 after increment: 0 error for Increment: try_lock failed because the operation would block after decrement: -1 after increment: 0 after decrement: -1 after increment: 0

The end result is still zero, so the error did not affect the overall outcome. The future just got polled again. While this has been interesting, we can mimic the exact same behavior using a higher level abstraction from a third-party crate such as Tokio for an easier implementation.

High-Level Data Sharing Between Futures

The future that we built in the previous section can be replaced with the following async function:

asyncfncount(count:u32,data:Arc<tokio::sync::Mutex<SharedData>>,counter_type:CounterType)->u32{for_in0..count{letmutdata=data.lock().await;matchcounter_type{CounterType::Increment=>{data.increment();println!("after increment: {}",data.counter);},CounterType::Decrement=>{data.decrement();println!("after decrement: {}",data.counter);}}std::mem::drop(data);std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));}returncount}

Here we merely loop through the total number acquiring the lock in an async way and sleeping to enable the second future to operate on the shared data. This can simply be run with the following code:

letshared_data=Arc::new(tokio::sync::Mutex::new(SharedData{counter:0}));letshared_two=shared_data.clone();lethandle_one:JoinHandle<u32>=tokio::task::spawn(asyncmove{count(3,shared_data,CounterType::Increment).await});lethandle_two:JoinHandle<u32>=tokio::task::spawn(asyncmove{count(3,shared_two,CounterType::Decrement).await});tokio::join!(handle_one,handle_two);

If we run this, we get the exact same printout and behavior as our futures in the previous section. However, it’s clearly simpler and easier to write. There are trade-offs to both approaches. For instance, if we just wanted to write futures that have the behavior we have coded, it would make sense to use just an async function. However, if we needed more control over how a future was polled, or we do not have access to an async implementation but we have a blocking function that tries, then it would make sense to write the poll function ourselves.

How Futures in Rust Are Different

Other languages implement futures for async programming, and some of these languages rely on the callback model. The callback model uses a function that fires when another function completes. This callback function is usually passed in as an argument to this function. This did not work for Rust because the callback model relies on dynamic dispatch, which means at runtime the exact function that was going to be called was determined at runtime as opposed to compile time. This produced additional overhead because the program had to work out what function to call at runtime. This violates the zero-cost approach and resulted in reduced performance.

Rust opted for an alternative approach with the aim of optimizing runtime performance by using the Future trait, which uses polls. The runtime is responsible for managing when to call polls. It does not need to schedule callbacks and worry about working out what function to call, instead it can use polls to see if the future is completed. This is more efficient because futures can be represented as a state machine in a single heap allocation, and the state machine captures local variables that are needed to execute the async function. This means there is one memory allocation per task, without any concern that the memory allocation will be the incorrect size. This decision is truly a testament to the Rust programming language, where the developers take the time to get the implementation right.

Oftentimes we are not using async/await in isolation and we want to do something else when a task is complete. We can specify this with specific combinators like and_then or or_else which are provided by Tokio.

How Are Futures Processed?

Let’s talk through how a future gets processed by walking through the steps at a high level:

- Create a future

-

A future can be created in multiple ways. One common approach is by defining an async function using the async keyword before the function. However, as we’ve seen earlier, you can also manually create a future by implementing the

Futuretrait yourself. When we call an async function, it returns a future. At this point, the future hasn’t performed any computation yet, and the await has not been called on it. - Spawn a task

-

We spawn a task with the future with

await, which means we register with an executor. The executor then takes responsibility for taking the task to completion. To do this, it maintains a queue of tasks. - Polling the task

-

The executor processes the futures in the task by calling the poll method. This is a feature of the

Futuretrait and will need to be implemented even if you are writing your own future. The future is either ready or it is still pending. - Schedules the next execution

-

If the future is not pending (i.e., not ready), the executor places the task back into the queue to be executed in the future.

- Completion of future

-

At some point, all the future in the task will complete, and the poll will return a ready. We should note that the result might be a Result or an Error. At this point, the executor can release any resources that it no longer needs and pass the results onwards.

Note on Async Runtimes

It must be noted that there are different variances of how async runtimes are implemented, and Tokio’s async runtime is much more complex and will be covered in Chapter 7.

We have now covered why we pin futures to prevent undefined behavior, context in futures, and data sharing between futures. To solidify what we have covered, we can move on to Chapter 3, where we implement what we covered in the tasks and futures sections in a practical project.

Putting It All Together

We have now covered tasks and futures and how they relate to async programming. We are now going to code a system that implements all that we have covered in this chapter. For our problem, we can conceive that we have a server or daemon that receives requests or messages. The data received needs to be logged to a file in case we need to inspect what happened. This problem means that we cannot predict when a log will happen. For instance, if we are just writing to a file in a single problem, our write operations can be blocking. However, receiving multiple requests from different programs can result in considerable overhead. It makes sense to send a write task to the async runtime and have the log written to the file when it is possible. It must be noted that this example is for educational purposes. While async writing to a file might be useful for a local application, if you have a server that is designed to take a lot of traffic, then you should explore database options.

In the following example, we are creating an audit trail for an application that logs interactions. This is an important part of many products that use sensitive data, like in the medical field. We want to log the user’s actions, but we do not want that logging action to hold up the program because we still want to facilitate a quick user experience. For this exercise to work, you will need the following dependencies:

[dependencies]tokio={version="1..39.0",features=["full"]}futures-util="0.3"

Using these dependencies, we need to import the following:

usestd::fs::{File,OpenOptions};usestd::io::prelude::*;usestd::sync::{Arc,Mutex};usestd::future::Future;usestd::pin::Pin;usestd::task::{Context,Poll};usetokio::task::JoinHandle;usefutures_util::future::join_all;

At this stage, pretty much all of this should make sense and you should be able to work out what we are using them for. We will be referring to the handle throughout the program, so we might as well define the type now with the following line:

typeAsyncFileHandle=Arc<Mutex<File>>;typeFileJoinHandle=JoinHandle<Result<bool,String>>;

Seeing as we do not want two tasks trying to write to the file at the same time, it makes sense to ensure that only one task has mutable access to the file at one time.

We may want to write to multiple files. For instance, we might want to write all logins to one file and error messages to another file. If you have medical patients in your system, you want to have a log file per patient (as you would probably inspect log files on a patient-by-patient basis), and you’d want to prevent unauthorized people looking at actions on a patient that they are not allowed to view. Considering there are needs for multiple files when logging, we can create a function that creates a file or obtains the handle of an existing file with the following code:

fnget_handle(file_path:&dynToString)->AsyncFileHandle{matchOpenOptions::new().append(true).open(file_path.to_string()){Ok(opened_file)=>{Arc::new(Mutex::new(opened_file))},Err(_)=>{Arc::new(Mutex::new(File::create(file_path.to_string()).unwrap()))}}}

Now that we have our file handles, we need to work on our future that will write to the log. The fields of the future take the following form:

structAsyncWriteFuture{pubhandle:AsyncFileHandle,pubentry:String}

We are now at a stage in our worked example where we can implement the Future trait for our AsyncWriteFuture struct and define the poll function. We will be using the same methods that we have covered in this chapter. Because of this, you can attempt to write the Future implementation and poll function yourself. Hopefully your implementation will look similar to this:

implFutureforAsyncWriteFuture{typeOutput=Result<bool,String>;fnpoll(self:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{letmutguard=matchself.handle.try_lock(){Ok(guard)=>guard,Err(error)=>{println!("error for {} : {}",self.entry,error);cx.waker().wake_by_ref();returnPoll::Pending}};letlined_entry=format!("{}\n",self.entry);matchguard.write_all(lined_entry.as_bytes()){Ok(_)=>println!("written for: {}",self.entry),Err(e)=>println!("{}",e)};Poll::Ready(Ok(true))}}

The Self::Output type is not super important to get right. We just decided it would be nice to have a true value to say it was written, but an empty bool or anything else works. The main focus of the previous code is that we try to get the lock for the file handle. If we do not manage to get the lock, we return a Pending. If we do get the lock, we write our entry to the file.

When it comes to writing to the log, it is not very intuitive for other developers to construct our future and spawn off a task into the async runtime. They just want to write to the log file. Therefore, we need to write our own write_log function that accepts the handle of the file and the line that is to be written to the log. Inside this function, we then spin off a Tokio task and return the handle of the task. This is a good opportunity for you to attempt to write this function yourself.

If you attempted to write the write_log function yourself, it should take a similar approach to the following code:

fnwrite_log(file_handle:AsyncFileHandle,line:String)->FileJoinHandle{letfuture=AsyncWriteFuture{handle:file_handle,entry:line};tokio::task::spawn(asyncmove{future.await})}

It must be noted that even though the function does not have async in front of the function definition, it still behaves like an async function. We can call it and get the handle, which we can then choose to await on later on in our program like so:

lethandle=write_log(file_handle,name.to_string());

Or we can directly await on it like this:

letresult=write_log(file_handle,name.to_string()).await;

We can now run our async logging functions with the following main function:

#[tokio::main]asyncfnmain(){letlogin_handle=get_handle(&"login.txt");letlogout_handle=get_handle(&"logout.txt");letnames=["one","two","three","four","five","six"];letmuthandles=Vec::new();fornameinnames{letfile_handle=login_handle.clone();letfile_handle_two=logout_handle.clone();lethandle=write_log(file_handle,name.to_string());lethandle_two=write_log(file_handle_two,name.to_string());handles.push(handle);handles.push(handle_two);}let_=join_all(handles).await;}

If you look at the printout, you will see something similar to the following code. We have not included the whole printout for brevity. We can see that six cannot be written to the file because of the try_lock(), but five is written successfully.:

. . . error for six : try_lock failed because the operation would block written for: five error for six : try_lock failed because the operation would block . . .

To make sure this has all worked in an async fashion, lets look at the login.txt file. Your file may have a different order, but mine looks like this:

onefourthreefivetwosix

You can see here that the numbers which were in order prior to entering the loop have been logged out of order in an async way.

And there we have it! We have built an async logging function that is wrapped up in a single function, making it easy to interface with. Hopefully this worked example has reinforced the concepts that we have covered in this chapter.

Summary

In this chapter, we’ve embarked on a journey through the landscape of asynchronous programming in Rust, highlighting the pivotal role of tasks. These units of asynchronous work, grounded in futures, are more than just technical constructs; they are the backbone of efficient concurrency in practice. For instance, consider the everyday task of preparing coffee and toast. By breaking it down into async blocks, we have seen firsthand that multitasking in code can be as practical and timesaving as in our daily routines.

However, async is not deterministic, meaning the execution order of async tasks is not set in stone, which, while initially daunting, opens a playground for optimization. Cooperative multitasking isn’t just a trick; it’s a strategy to get the most out of our resources, something we’ve applied to accelerate our async operations.

We have also covered the sharing of data between tasks, which can be a double-edged sword. It’s tempting to think that access to data is a nice tool for designing our solution, but without careful control, as demonstrated with our Mutex examples, it can lead to unforeseen delays and complexity. Here lies a valuable lesson: shared state must be managed, not just for the sake of order but for the sanity of our code’s flow.

Finally, our look into the Future trait was more than an academic exercise; it offered us a lens to understand and control the intricacies of task execution. It’s a reminder that power comes with responsibility—the power to control task polling comes with the responsibility to understand the impact of each await expression.

As we move forward, remember that implementing and utilizing async operations is not just about putting tasks into motion. It’s about grasping the underlying dynamics of each async expression. We can understand the underlying dynamics further by constructing our own async queues in Chapter 3. There, you will gain the insights needed to define and control asynchronous workflows in Rust.