Chapter 10. Building an Async Server with No Dependencies

We are now at the penultimate chapter of this book. Therefore, we need to focus on understanding how async interacts in a system. To do this, we are going to build an async server completely from the standard library with no third-party dependencies. This will solidify your understanding of the fundamentals of async programming and how it fits into the bigger picture of a software system. Packages, programming languages, and API documentation will change over time. While understanding the current tools of async is important, and we have covered them throughout the book, knowing the fundamentals of async programming will enable you to read new documentation/tools/frameworks/languages you come across with ease.

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to build a multithreaded TCP server that will accept incoming requests and send these requests to an async executor to be processed asynchronously. Because we are only using the standard library, you will also be able to build your own async executor that accepts tasks and keeps polling them to completion. Finally, you will also be able to implement this async functionality to a client that sends requests to the server. This will give you the ability and confidence to build basic async solutions with minimal dependencies to solve lightweight problems. So, let’s get started with setting up the basics of this project.

Setting Up the Basics

For our project, we are going to use four workspaces which are defined in the root directory Cargo.toml:

[workspace]members=["client","server","data_layer","async_runtime"]

The reason why we have four workspaces is that these modules have a fair amount of crossover use. The client and server are going to be separate in order to call them separately. Both server and client are going to use our async runtime, so this needs to be separate. The data_layer is merely a message struct that serializes and deserializes itself. It needs to be in a separate workspace because both client and server are going to reference the data struct. We can write our boilerplate code in data_layer/src/data.rs, with the following layout:

usestd::io::{self,Cursor,Read,Write};#[derive(Debug)]pubstructData{pubfield1:u32,pubfield2:u16,pubfield3:String,}implData{pubfnserialize(&self)->io::Result<Vec<u8>>{...}pubfndeserialize(cursor:&mutCursor<&[u8]>)->io::Result<Data>{...}}

The serialize and deserialize functions enable us to send the Data struct over TCP connections. We can use serde if we want to do more complicated structs, but in the spirit of this chapter, we are writing our own serialization logic because our entire application is not going to have any dependencies. Do not worry, this is the only part of non-async boilerplate code that we are going to write. Our serialize function takes the following form:

letmutbytes=Vec::new();bytes.write(&self.field1.to_ne_bytes())?;bytes.write(&self.field2.to_ne_bytes())?;letfield3_len=self.field3.len()asu32;bytes.write(&field3_len.to_ne_bytes())?;bytes.extend_from_slice(self.field3.as_bytes());Ok(bytes)

We use 4 bytes for each number, and another 4-byte integer to dictate the length of the string, as the length of strings can vary.

For our deserialize function, we pass in arrays and vectors with the correct capacity into the array of bytes to read and convert them to the right format:

// Initialize buffers for the fields, using arrays of the appropriate sizeletmutfield1_bytes=[0u8;4];letmutfield2_bytes=[0u8;2];// Read the first field (4 bytes) from the cursor into the buffer.// Do the same for second field.cursor.read_exact(&mutfield1_bytes)?;cursor.read_exact(&mutfield2_bytes)?;// Convert the byte arrays into the appropriate data types (u32 and u16)letfield1=u32::from_ne_bytes(field1_bytes);letfield2=u16::from_ne_bytes(field2_bytes);// Initialize a buffer to read the length of the third field,// which is 4 bytes longletmutlen_bytes=[0u8;4];// Read the length from the cursor into the buffercursor.read_exact(&mutlen_bytes)?;// Convert the length bytes into a usizeletlen=u32::from_ne_bytes(len_bytes)asusize;// Initialize a buffer with the specified length to hold the third field's dataletmutfield3_bytes=vec![0u8;len];// Read the third field's data from the cursor into the buffercursor.read_exact(&mutfield3_bytes)?;// Convert the third field's bytes into a UTF-8 string, or// return an error if this cannot be done.letfield3=String::from_utf8(field3_bytes).map_err(|_|io::Error::new(io::ErrorKind::InvalidData,"Invalid UTF-8"))?;// Return the structured dataOk(Data{field1,field2,field3})

With our data layer logic completed, we make our Data struct public in the data_layer/src/lib.rs file:

pubmoddata;

With our data layer completed, we can move on to the interesting stuff: building our async runtime from just the standard library.

Building Our std Async Runtime

To build the async components for our server, we need the following components in order:

-

Waker: waking up futures to be resumed

-

Executor: processing futures to completion

-

Sender: async future enabling async sending of data

-

Receiver: async future enabling async receiving of data

-

Sleeper: async future enabling async sleeping of a task

Seeing as we need the waker to help the executor reanimate tasks to be polled again, we will start with building our waker.

Building Our Waker

We have used the waker throughout the book when implementing the Future trait, and we know instinctively that the wake or wake_by_ref function is required to allow the future to be polled again. Therefore, the waker is our obvious first choice because futures and the executor will handle the waker. To build our waker, we start with the following import in our async_runtime/src/waker.rs file:

usestd::task::{RawWaker,RawWakerVTable};

We then build our waker table:

staticVTABLE:RawWakerVTable=RawWakerVTable::new(my_clone,my_wake,my_wake_by_ref,my_drop,);

We can call the functions whatever we want as long as they have the correct function signatures. RawWakerTable is a virtual function pointer table that RawWaker points to and calls to perform operations throughout its lifecycle. For instance, if the clone function is called on RawWaker, the my_clone function in RawWakerTable will be called. We are going to keep the implementation of these functions as basic as possible, but we can see how RawWakerTable can be utilized. For instance, data structures that have static lifetimes and are thread-safe could keep track of the wakers in our system by interacting with the functions in RawWakerTable.

We can start with our clone function. This usually gets called when we poll a function, as we need to clone an atomic reference of our waker in our executor to wrap in a context and pass into the future being polled. Our clone implementation takes the following form:

unsafefnmy_clone(raw_waker:*const())->RawWaker{RawWaker::new(raw_waker,&VTABLE)}

Our wake and wake_by_ref functions are called when the future should be polled again because the future that is being waited on is ready. For our project, we are going to be polling our futures without being prompted by the waker to see if they are ready, so our simple implementation is defined here:

unsafefnmy_wake(raw_waker:*const()){drop(Box::from_raw(raw_wakeras*mutu32));}unsafefnmy_wake_by_ref(_raw_waker:*const()){}

The my_wake function converts the raw pointer back to a box and drops it. This makes sense because my_wake is supposed to consume the waker. The my_wake_by_ref function does nothing. It is the same as the my_wake function but does not consume the waker. If we wanted to experiment with notifying the executor, we could have an AtomicBool that we set to true in these functions. Then we can come up with some form of executor mechanism to check the AtomicBool before bothering to poll the future, as checking an AtomicBool is less computationally expensive than polling a future. We could also have another queue where a notification could be sent for task readiness, but for our server implementation, we are going to stick with polling without checking before the poll is performed.

When our task has finished or has been canceled, we no longer need to poll our task, and our waker is dropped. Our drop function takes the following form:

unsafefnmy_drop(raw_waker:*const()){drop(Box::from_raw(raw_wakeras*mutu32));}

This is where we convert the box back to a raw pointer and drop it.

We have now defined all the functions for our waker. All we need is a function to create the waker:

pubfncreate_raw_waker()->RawWaker{letdata=Box::into_raw(Box::new(42u32));RawWaker::new(dataas*const(),&VTABLE)}

We pass in some dummy data and create RawWaker with a reference to our function table. We can see the customization that we have with this raw approach. We could have multiple RawWakerTable definitions, and we could construct different function tables than RawWaker, depending on what we pass into the create_raw_waker function. In our executor, we could vary the input depending on the type of future we are processing. We could also pass in a reference to a data structure that our executor is holding instead of the u32 number 42. The number 42 has no significance; it is just an example of data being passed in. The data structure passed in could then be referenced in our functions bound to the table.

Even though we have built the bare bones of a waker, we can appreciate the power and customization that we have for choosing to build our own. Considering we need to use our waker to execute tasks in our executor, we can now move on to building our executor.

Building Our Executor

At a high level, our executor is going to consume futures, turn them into tasks so they can be run by our executor, return a handle, and put the task on a queue. Periodically, our executor is also going to poll tasks on that queue. We are going to house our executor in our async_runtime/src/executor.rs file. First, we need the following imports:

usestd::{future::Future,sync::{Arc,mpsc},task::{Context,Poll,Waker},pin::Pin,collections::VecDeque};usecrate::waker::create_raw_waker;

Before we begin to write our executor, we need to define our task struct that is going to be passed around the executor:

pubstructTask{future:Pin<Box<dynFuture<Output=()>+Send>>,waker:Arc<Waker>,}

Something might seem off to you when looking at the Task struct, and you would be right. Our future in our Task struct returns a (). However, we want to be able to run tasks that return different data types. The runtime would be terrible if we could only return one data type. You might feel the need to pass in a generic parameter, resulting in the following code:

pubstructTask<T>{future:Pin<Box<dynFuture<Output=T>+Send>>,waker:Arc<Waker>,}

However, what happens with generics is that the compiler will look at all the instances of Task<T> and generate structs for every variance of T. Also, our executor will need the T generic argument to process Task<T>. This will result in multiple executors for each variance of T, which would result in a mess. Instead, we wrap our future in an async block, get the result of the future, and send that result over a channel. Therefore, our signature of all tasks return (), but we can still extract the result from the future. We will see how this is implemented in the spawn function on our executor. Here is the outline for our executor:

pubstructExecutor{pubpolling:VecDeque<Task>,}implExecutor{pubfnnew()->Self{Executor{polling:VecDeque::new(),}}pubfnspawn<F,T>(&mutself,future:F)->mpsc::Receiver<T>whereF:Future<Output=T>+'static+Send,T:Send+'static,{...}pubfnpoll(&mutself){...}pubfncreate_waker(&self)->Arc<Waker>{Arc::new(unsafe{Waker::from_raw(create_raw_waker())})}}

The polling field of the Executor is where we are going to put our spawned tasks to be polled.

Note

Take note of our create_waker function in our Executor. Remember, our Executor is running on one thread and can only process one future at a time. If our Executor houses a data collection, we can pass a reference through to the create_raw_waker function if we have configured create_raw_waker to handle it. Our waker can have unsafe access to the data collection because only one future is being processed at a time, so there is not going to be more than one mutable reference from a future at a time.

Once a task is polled, if the task is still pending, we will put the task back on the polling queue to be polled again. To initially put the task on the queue, we use the spawn function:

pubfnspawn<F,T>(&mutself,future:F)->mpsc::Receiver<T>whereF:Future<Output=T>+'static+Send,T:Send+'static,{let(tx,rx)=mpsc::channel();letfuture:Pin<Box<dynFuture<Output=()>+Send>>=Box::pin(asyncmove{letresult=future.await;let_=tx.send(result);});lettask=Task{future,waker:self.create_waker(),};self.polling.push_back(task);rx}

We use the channel to return a handle and convert the return value of the future to ().

Note

If exposing the internal channel is not your style, you can create the following JoinHandle struct for the spawn task to return:

pubstructJoinHandle<T>{receiver:mpsc::Receiver<T>,}impl<T>JoinHandle<T>{pubfnawait(self)->Result<T,mpsc::RecvError>{self.receiver.recv()}}

Give your return handle the following await syntax:

matchhandle.await(){Ok(result)=>println!("Received: {}",result),Err(e)=>println!("Error receiving result: {}",e),}

Now that we have our task on our polling queue, we can poll it with the Executor’s polling function:

pubfnpoll(&mutself){letmuttask=matchself.polling.pop_front(){Some(task)=>task,None=>return,};letwaker=task.waker.clone();letcontext=&mutContext::from_waker(&waker);matchtask.future.as_mut().poll(context){Poll::Ready(())=>{}Poll::Pending=>{self.polling.push_back(task);}}}

We just pop the task from the front of the queue, wrap a reference of our waker in a context, and pass that into the poll function of the future. If the future is ready, we do not need to do anything, as we are sending the result back via a channel so the future is dropped. If our future is pending, we just put it back on the queue.

The backbone of our async runtime is now done, and we can run async code. Before we build the rest of our async_runtime module, we should take a detour and run our executor. Not only must you be excited to see it work, but you may want to play around with customizing how futures are processed. Now is a good time to get a feel for how our system works.

Running Our Executor

Running our async runtime is fairly straightforward. In the main.rs file of our async_runtime module, we import the following:

usestd::{future::Future,task::{Context,Poll},pin::Pin};modexecutor;modwaker;

We need a basic future to trace how our system is running. We have been using the counting future throughout the book, as it is such an easy implementation of a future that returns either Pending or Ready depending on the state. For quick reference (hopefully you can code this from memory now), the counting future takes this form:

pubstructCountingFuture{pubcount:i32,}implFutureforCountingFuture{typeOutput=i32;fnpoll(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{self.count+=1;ifself.count==4{println!("CountingFuture is done!");Poll::Ready(self.count)}else{cx.waker().wake_by_ref();println!("CountingFuture is not done yet! {}",self.count);Poll::Pending}}}

We define our futures, define our executor, spawn our futures, and then run them with the following code:

fnmain(){letcounter=CountingFuture{count:0};letcounter_two=CountingFuture{count:0};letmutexecutor=executor::Executor::new();lethandle=executor.spawn(counter);let_handle_two=executor.spawn(counter_two);std::thread::spawn(move||{loop{executor.poll();}});letresult=handle.recv().unwrap();println!("Result: {}",result);}

We spawn a thread and run an infinite loop polling the futures in the executor. While this loop is happening, we wait for the result of one of the futures. In our server, we will implement our executors properly so they can continue to receive futures throughout the entire lifetime of the program. This quick implementation gives us the following printout:

CountingFuture is not done yet! 1 CountingFuture is not done yet! 1 CountingFuture is not done yet! 2 CountingFuture is not done yet! 2 CountingFuture is not done yet! 3 CountingFuture is not done yet! 3 CountingFuture is done! CountingFuture is done! Result: 4

We can see that it works! We have an async runtime running with just the standard library!

Note

Remember that our waker does not really do anything. We are polling our futures in our executor queue regardless. If you comment out the cx.waker().wake_by_ref(); line in the poll function of CountingFuture, you will get the exact same result, which is different from what happens in runtimes like smol or Tokio. This tells us that established runtimes are using the waker to only poll futures that are to be woken. This means that established runtimes are more efficient with their polling.

Now that we have our async runtime running, we can drag the rest of our async processes over the finish line. We can start with a sender.

Building Our Sender

When it comes to sending data over a TCP socket, we must allow our executor to switch over to another async task if the connection is currently blocked. If the connection is not blocked, we can write the bytes to the stream. In our async_runtime/src/sender.rs file, we start by importing the following:

usestd::{future::Future,task::{Context,Poll},pin::Pin,net::TcpStream,io::{self,Write},sync::{Arc,Mutex}};

Our sender is essentially a future. During the poll function, if the stream is blocking, we will return Pending; if the stream is not blocking, we write the bytes to the stream. Our sender structure is defined here:

pubstructTcpSender{pubstream:Arc<Mutex<TcpStream>>,pubbuffer:Vec<u8>}implFutureforTcpSender{typeOutput=io::Result<()>;fnpoll(self:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{...}}

Our TcpStream is wrapped in Arc<Mutex<T>>. We use Arc<Mutex<T>> so we can pass TcpStream into Sender and Receiver. Once we have sent the bytes over the stream, we will want to employ a Receiver future to await for the response.

For our poll function in the TcpSender struct, we initially try to get the lock of the stream:

letmutstream=matchself.stream.try_lock(){Ok(stream)=>stream,Err(_)=>{cx.waker().wake_by_ref();returnPoll::Pending;}};

If we cannot get the lock, we return Pending so we are not blocking the executor, and the task will be put back on the queue to be polled again. Once we have it, we set it to nonblocking:

stream.set_nonblocking(true)?;

The set_nonblocking function makes the stream return a result immediately from the write, recv, read, or send functions. If the I/O operation was successful, the result will be Ok. If the I/O operation returns an io::ErrorKind::WouldBlock error, the IO operation needs to be retried because the stream was blocking. We handle these I/O operation outcomes as follows:

matchstream.write_all(&self.buffer){Ok(_)=>{Poll::Ready(Ok(()))},Err(refe)ife.kind()==io::ErrorKind::WouldBlock=>{cx.waker().wake_by_ref();Poll::Pending},Err(e)=>Poll::Ready(Err(e))}

We now have a sender future defined, so we can move on to our receiver future.

Building Our Receiver

Our receiver will wait for the data in the stream, returning Pending if the bytes are not in the stream to be read. To build this future, we import the following in the async_runtime/src/reciever.rs file:

usestd::{future::Future,task::{Context,Poll},pin::Pin,net::TcpStream,io::{self,Read},sync::{Arc,Mutex}};

Seeing as we are returning bytes, it will not be a surprise that our receiver future takes this form:

pubstructTcpReceiver{pubstream:Arc<Mutex<TcpStream>>,pubbuffer:Vec<u8>}implFutureforTcpReceiver{typeOutput=io::Result<Vec<u8>>;fnpoll(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{...}}

In our poll function, we acquire the lock of the stream and set it to nonblocking, just like we did in our sender future:

letmutstream=matchself.stream.try_lock(){Ok(stream)=>stream,Err(_)=>{cx.waker().wake_by_ref();returnPoll::Pending;}};stream.set_nonblocking(true)?;

Next we handle the read of the stream:

letmutlocal_buf=[0;1024];matchstream.read(&mutlocal_buf){Ok(0)=>{Poll::Ready(Ok(self.buffer.to_vec()))},Ok(n)=>{std::mem::drop(stream);self.buffer.extend_from_slice(&local_buf[..n]);cx.waker().wake_by_ref();Poll::Pending},Err(refe)ife.kind()==io::ErrorKind::WouldBlock=>{cx.waker().wake_by_ref();Poll::Pending},Err(e)=>Poll::Ready(Err(e))}

We now have all the async functionality to get our server running. However, there is one basic future that we can build to allow sync code to also have async properties: the sleep future.

Building Our Sleep

We covered this before, so hopefully you are able to implement this yourself. However, for reference, our async_runtime/src/sleep.rs file will house our sleep future. We import the following:

usestd::{future::Future,pin::Pin,task::{Context,Poll},time::{Duration,Instant},};

Our Sleep struct takes this form:

pubstructSleep{when:Instant,}implSleep{pubfnnew(duration:Duration)->Self{Sleep{when:Instant::now()+duration,}}}

And our Sleep future implements the Future trait:

implFutureforSleep{typeOutput=();fnpoll(self:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{letnow=Instant::now();ifnow>=self.when{Poll::Ready(())}else{cx.waker().wake_by_ref();Poll::Pending}}}

Now our async system has everything we need. To make our async runtime components public, we have the following code in our async_runtime/src/lib.rs file:

pubmodexecutor;pubmodwaker;pubmodreciever;pubmodsleep;pubmodsender;

We can now import our components into our server. Considering that all the functionality is completed, we should use it to build our server.

Building Our Server

To build our server, we need the data and async modules that we coded. To install these, the Cargo.toml file dependencies take the following form:

[dependencies]data_layer={path="../data_layer"}async_runtime={path="../async_runtime"}[profile.release]opt-level='z'

We are optimizing for binary size with opt-level.

The entire code for our server can be in our main.rs file, which needs these imports:

usestd::{thread,sync::{mpsc::channel,atomic::{AtomicBool,Ordering}},io::{self,Read,Write,ErrorKind,Cursor},net::{TcpListener,TcpStream}};usedata_layer::data::Data;useasync_runtime::{executor::Executor,sleep::Sleep};

Now that we have everything we need, we can build out the code that will accept our requests.

Accepting Requests

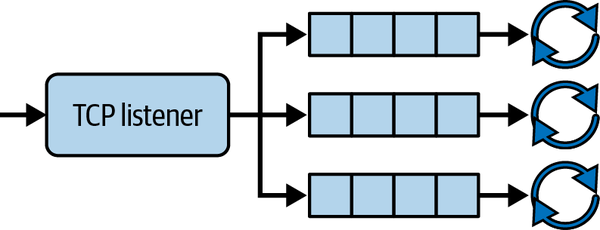

We can have our main thread listening to incoming TCP requests. Then our main thread distributes the requests along three threads and executors, as depicted in Figure 10-1.

Figure 10-1. Handling incoming requests

We also want our threads to park if there are no requests to process. To communicate with the threads for parking, we have an AtomicBool for each thread:

staticFLAGS:[AtomicBool;3]=[AtomicBool::new(false),AtomicBool::new(false),AtomicBool::new(false),];

Each AtomicBool represents a thread. If the AtomicBool is false, the thread is not parked. If the AtomicBool is true, then our router knows that our thread is parked and that we have to wake it up before sending the thread a request.

Now that we have our FLAGS, we must handle our incoming requests for each thread. Inside our threads, we create an executor and then try to receive a message in the channel for the thread. If there is a request in the channel, we spawn a task on that executor. If there is no incoming request, we check for tasks waiting to be polled. If there are no tasks, then the thread sets FLAG to true and parks the thread. If there are any tasks to be polled, then we poll the task at the end of the loop. We can carry out this process with this macro:

macro_rules!spawn_worker{($name:expr,$rx:expr,$flag:expr)=>{thread::spawn(move||{letmutexecutor=Executor::new();loop{ifletOk(stream)=$rx.try_recv(){println!("{} Received connection: {}",$name,stream.peer_addr().unwrap());executor.spawn(handle_client(stream));}else{ifexecutor.polling.len()==0{println!("{} is sleeping",$name);$flag.store(true,Ordering::SeqCst);thread::park();}}executor.poll();}})};}

Here in our macro, we accept the name of our thread for logging purposes, the receiver of a channel to accept incoming requests, and the flag to inform the rest of the system when the thread parks.

Note

You can read more about creating complex macros in “Writing Complex Macros in Rust” by Ingvar Stepanyan.

We can orchestrate the accepting of our requests in the main function:

fnmain()->io::Result<()>{...Ok(())}

First, we define the channels that we will use to send requests to our threads:

let(one_tx,one_rx)=channel::<TcpStream>();let(two_tx,two_rx)=channel::<TcpStream>();let(three_tx,three_rx)=channel::<TcpStream>();

We then create our threads for our requests to be handled:

letone=spawn_worker!("One",one_rx,&FLAGS[0]);lettwo=spawn_worker!("Two",two_rx,&FLAGS[1]);letthree=spawn_worker!("Three",three_rx,&FLAGS[2]);

Now our executors are running in their own threads and waiting for our TCP listener to send them requests. We need to keep and reference the thread handles and thread channel transmitters so we can wake and send requests to individual threads. We can interact with the threads by using the following code:

letrouter=[one_tx,two_tx,three_tx];letthreads=[one,two,three];letmutindex=0;letlistener=TcpListener::bind("127.0.0.1:7878")?;println!("Server listening on port 7878");forstreaminlistener.incoming(){...}

All we need to do now is handle our incoming TCP requests:

forstreaminlistener.incoming(){matchstream{Ok(stream)=>{let_=router[index].send(stream);ifFLAGS[index].load(Ordering::SeqCst){FLAGS[index].store(false,Ordering::SeqCst);threads[index].thread().unpark();}index+=1;// cycle through the index of threadsifindex==3{index=0;}}Err(e)=>{println!("Connection failed: {}",e);}}}

Once we receive the TCP request, we send the TCP stream to a thread, check whether the thread is parked, and unpark the thread if needed. Next, we move the index over to the next thread so we can distribute the requests evenly across all our threads.

So what do we do with the requests once we have sent the request to an executor? We handle them.

Handling Requests

When it comes to handling our requests, we recall that our handle_stream function is called in the executor. Our handle async function takes the following form:

asyncfnhandle_client(mutstream:TcpStream)->std::io::Result<()>{stream.set_nonblocking(true)?;letmutbuffer=Vec::new();letmutlocal_buf=[0;1024];loop{...}matchData::deserialize(&mutCursor::new(buffer.as_slice())){Ok(message)=>{println!("Received message: {:?}",message);},Err(e)=>{println!("Failed to decode message: {}",e);}}Sleep::new(std::time::Duration::from_secs(1)).await;stream.write_all(b"Hello, client!")?;Ok(())}

This should look similar to the sender and receiver futures that we built in the async runtime. Here, we add our async sleep for 1 second. This is just to simulate work being done. This will also ensure that our async is working. If our async is not properly working and we send 10 requests, then the total time will be above 10 seconds.

Inside our loop, we process the incoming stream:

matchstream.read(&mutlocal_buf){Ok(0)=>{break;},Ok(len)=>{buffer.extend_from_slice(&local_buf[..len]);},Err(refe)ife.kind()==ErrorKind::WouldBlock=>{ifbuffer.len()>0{break;}Sleep::new(std::time::Duration::from_millis(10)).await;continue;},Err(e)=>{println!("Failed to read from connection: {}",e);}}

If blocking occurs, we introduce a tiny async sleep so the executor will put the request handle back on the queue to poll other request handles.

Our server is now fully functioning. The only piece left that we need to code is our client.

Building Our Async Client

Because our client also relies on the same dependencies, it will not be surprising that the client Cargo.toml has the following dependencies:

[dependencies]data_layer={path="../data_layer"}async_runtime={path="../async_runtime"}

In our main.rs file, we need the following imports:

usestd::{io,sync::{Arc,Mutex},net::TcpStream,time::Instant};usedata_layer::data::Data;useasync_runtime::{executor::Executor,reciever::TcpReceiver,sender::TcpSender,};

To send, we implement the sending and receiving futures from our async runtime:

asyncfnsend_data(field1:u32,field2:u16,field3:String)->io::Result<String>{letstream=Arc::new(Mutex::new(TcpStream::connect("127.0.0.1:7878")?));letmessage=Data{field1,field2,field3};TcpSender{stream:stream.clone(),buffer:message.serialize()?}.await?;letreceiver=TcpReceiver{stream:stream.clone(),buffer:Vec::new()};String::from_utf8(receiver.await?).map_err(|_|io::Error::new(io::ErrorKind::InvalidData,"Invalid UTF-8"))}

We can now call our async send_data function 4,000 times and wait on all those handles:

fnmain()->io::Result<()>{letmutexecutor=Executor::new();letmuthandles=Vec::new();letstart=Instant::now();foriin0..4000{lethandle=executor.spawn(send_data(i,iasu16,format!("Hello, server! {}",i)));handles.push(handle);}std::thread::spawn(move||{loop{executor.poll();}});println!("Waiting for result...");forhandleinhandles{matchhandle.recv().unwrap(){Ok(result)=>println!("Result: {}",result),Err(e)=>println!("Error: {}",e)};}letduration=start.elapsed();println!("Time elapsed in expensive_function() is: {:?}",duration);Ok(())}

And our test is ready. If you run the server and client in different terminals, you will see that all the printouts display that the requests are being handled. The entire client process takes roughly 1.2 seconds, meaning that our async system is running. And there you have it! We have built an async server with zero third-party dependencies!

Summary

In this chapter, we used only the standard library to build an async runtime that is fairly efficient. Part of this performance is a result of us coding our server in Rust. Another factor is that the async module increases the utilization of our resources for I/O bound tasks like connections. Sure, our server is not going to be as efficient as runtimes like Tokio, but it is usable.

We do not advise that you start ripping Tokio and web frameworks out of your projects since a lot of crates have been built to integrate with runtimes like Tokio. You would lose a lot of integration with third-party crates, and your runtime would not be as efficient. However, you can also have another runtime active in your program at the same time. For instance, we can use Tokio channels to send tasks to our custom async runtime. This means that Tokio can juggle other async Tokio tasks while awaiting the completion of the task in our custom async runtime. This approach is useful when you need an established runtime like Tokio to handle standard async tasks like incoming requests, but you also have specific need to handle tasks in a very particular way for a niche problem. For instance, you may have built a key-value store and have read up on the latest computer science papers on how to handle transactions on it. You then want to directly implement that logic in your custom async runtime.

We can conclude that building our own async runtime isn’t the best or worst approach. Knowing established runtimes and being able to build your own is the best of both worlds. Having both tools at hand and knowing where and when to apply them is way better than being an evangelist for one tool. However, you need to practice these tools before you whip them out and use them to solve a problem. We suggest that you continue pushing yourself with custom async runtimes on a range of projects. Experimenting with different types of data around the waker is a good start to explore multiple approaches.

Testing is a big part of exploring and refining your approaches. Testing enables you to get in-depth, direct feedback on your async code and implementation. In Chapter 11, we will cover how to test your async code so you can continue exploring async concepts and implementations.