Chapter 5. Coroutines

At this stage in the book, you should be comfortable with async programming. When you see await syntax in code now, you know what is happening under the hood with futures, tasks, threads, and queues. However, what about the building blocks of async programming? What if we can get our code to pause and resume without having to use an async runtime? Furthermore, what if we can use this pause-and-resume mechanism to test our code by using normal tests? These tests can explore how code behaves under various polling orders and configurations. Our pause-and-resume mechanism can also be the interface between synchronous code and async. This is where coroutines come in.

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to define a coroutine and explain how they can be used. You should be able to integrate coroutines into your own programs to keep memory consumption low for tasks that would require large amounts of memory. You will also be able to mimic async functionality without an async runtime by using coroutines and implement a basic executor. This results in getting async functionality in your main thread without the need for an async runtime. You will also be able to gain fine-grained control over when and in what order your coroutines get polled.

Note

At the time of this writing, we are using the coroutine syntax in nightly Rust. The syntax might have changed, or the coroutine syntax might have made its way to stable Rust. Although changing syntax is annoying, it is the fundamentals of coroutines that we are covering in this chapter. S syntax changes will not affect the overall implementation of coroutines and how we can use them.

Introducing Coroutines

Before we can fully explore coroutines, you need to understand what a coroutine is and why you’d want to use it.

What Are Coroutines?

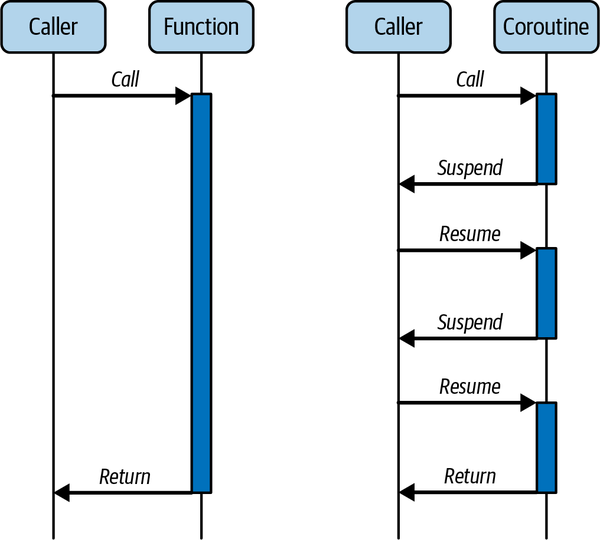

A coroutine is a special type of program that can pause its execution and then at a later point in time resume from where it left off. This is different from regular subroutines (like functions), which run to completion and typically return a value or throw an error. Figure 5-1 illustrates the comparison.

Figure 5-1. A regular subroutine (left) versus a coroutine (right)

Let’s compare a coroutine to a subroutine. After a subroutine starts, it executes from the start to the end, and any particular instance of a subroutine returns just one time. A coroutine is different, as it can exit in multiple ways. It can finish like a subroutine, but it can also exit by calling another coroutine (called yielding) and then returning later to the same point. Therefore, a coroutine keeps track of the state by storing it during the pause.

A coroutine is not unique to Rust, and many implementations of coroutines exist in different languages. They all share the same basic features to allow for pausing and resuming execution:

- Nonblocking

-

When coroutines get paused, they do not block the thread of execution.

- Stateful

-

Coroutines can store their state when they are paused and then continue from that state when they are resumed. There is no need to start from the beginning.

- Cooperative

-

Coroutines can pause and be resumed at a later stage in a controlled manner.

Now let’s think about how coroutines are similar to threads. On the face of it, they seem quite similar—executing tasks and later pausing/resuming. The difference is in the scheduling. A thread is scheduled preemptively: the task is interrupted by an external scheduler with the aim that the task will be resumed later. In contrast, a coroutine is cooperative: it can pause or yield to another coroutine without a scheduler or the OS getting involved.

Using coroutines sounds great, so why bother with async/await at all? As with anything in programming, trade-offs exist here. Let’s run through some pros to start with. Coroutines remove the need for syncing primitives like mutexes, as the coroutines are running in the same thread. This can make it easier to understand and write the code, not an insignificant consideration. Switching back and forth between coroutines in one thread is much cheaper than switching between threads. It is particularly useful for tasks where you might spend a lot of time waiting. Imagine that you need to keep track of changes in 100 files. Having the OS schedule 100 threads that loop through and check each file would be a pain. Context switching is computationally expensive. It would be more efficient and easier instead to have 100 coroutines checking whether the file they are monitoring has changed and then sending that file into a thread pool to be processed when it has.

The major downside to using coroutines in just one thread is that you are not taking advantage of the power of your computer. Running a program in one thread means you are not splitting tasks across multiple cores. Now that you know what coroutines are, let’s explore why we should use them.

Why Use Coroutines?

At a high level, coroutines enable us to suspend an operation, yield control back to the thread that executed the coroutine, and then resume the operation when needed. This sounds a lot like async. An async task can yield control for another task to be executed through polling. With multithreading, we can send data to the thread and check in on the thread as needed through channels and data structures wrapped in Sync primitives. Coroutines, on the other hand, enable us to suspend an operation and resume with the waker without needing an async runtime or thread.

This may seem a little abstract, but we should illustrate the advantages of using a coroutine with a simple file-writing example. Let’s imagine that we are getting a lot of integers and we need to write them to a file. Perhaps we are getting numbers from another program, and we can’t wait for all the numbers to be received before we start writing, as this would take up too much memory.

For our exercise, we need the following dependency:

[dependencies]rand="0.8.5"

Before we write the code for our demonstration, we need the following imports:

#![feature(coroutines)]#![feature(coroutine_trait)]usestd::fs::{OpenOptions,File};usestd::io::{Write,self};usestd::time::Instant;userand::Rng;usestd::ops::{Coroutine,CoroutineState};usestd::pin::Pin;

We also need the rand crate in our Cargo.toml. These imports might seem a little excessive for a simple write exercise, but you will see how they are utilized when we move through this example. The macros are there to allow the experimental features. For our simple file-writing example, we have the following function:

fnappend_number_to_file(n:i32)->io::Result<()>{letmutfile=OpenOptions::new().create(true).append(true).open("numbers.txt")?;writeln!(file,"{}",n)?;Ok(())}

This function opens the file and writes to it. We now want to test it and measure our performance, so we generate 200 thousand random integers and loop through them, writing to the file. We also time this operation with the following code:

fnmain()->io::Result<()>{letmutrng=rand::thread_rng();letnumbers:Vec<i32>=(0..200000).map(|_|rng.gen()).collect();letstart=Instant::now();for&numberin&numbers{ifletErr(e)=append_number_to_file(number){eprintln!("Failed to write to file: {}",e);}}letduration=start.elapsed();println!("Time elapsed in file operations is: {:?}",duration);Ok(())}

At the time of this writing, the test took 4.39 seconds to complete. This is not very fast; however, this is because we are opening the file every time, which has the overhead of checking permissions and updating the file’s metadata.

We can now employ a coroutine to handle the writing of the integers. First, we define the struct that houses the file descriptor:

structWriteCoroutine{pubfile_handle:File,}implWriteCoroutine{fnnew(path:&str)->io::Result<Self>{letfile_handle=OpenOptions::new().create(true).append(true).open(path)?;Ok(Self{file_handle})}}

We then implement the Coroutine trait:

implCoroutine<i32>forWriteCoroutine{typeYield=();typeReturn=();fnresume(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,arg:i32)->CoroutineState<Self::Yield,Self::Return>{writeln!(self.file_handle,"{}",arg).unwrap();CoroutineState::Yielded(())}}

Our coroutine, as indicated by the types type Yield = (); and type Return = ();, is structured so that it neither yields intermediate values nor returns a final result. We can cover this later, but what is important is that we return CoroutineState::Yielded. This is like returning Pending in a future, but the Yield type is returned. We can also return CoroutineState::Complete, which is like Ready in a future.

In our test, we can then create our coroutine and loop through the numbers, calling the resume function with this code:

letmutcoroutine=WriteCoroutine::new("numbers.txt")?;for&numberin&numbers{Pin::new(&mutcoroutine).resume(number);}

Our updated test will give us a time of roughly 622.6 ms. This is roughly six times faster. Sure, we could have just created the file descriptor and referenced it in the loop to get the same effect, but this demonstrates that there is a benefit to suspending the state of a coroutine and resuming it when needed. We managed to keep our write logic isolated, but we did not need any threads or async runtimes for that speedup. Coroutines can be building blocks within threads and async tasks to suspend resume computations.

Note

You may have noticed similarities between implementing the Future trait and Coroutine trait. There are two possible states, you resume or finish depending on the two possible outcomes, and you suspend and resume both coroutines and async tasks. It could be argued that async tasks are coroutines in a general sense, with the difference being that they are sent to a different thread and polled by an executor.

Coroutines have a lot of uses. They could be used to handle network requests, big data processing, or UI applications. They provide a simpler way of handling async tasks compared to using callbacks. Using coroutines, we can implement async functionality in one thread without the need for queues or a defined executor.

Generating with Coroutines

You may have come across the concept of generators in other languages such as Python. Generators are a subset of coroutines, sometimes called weak coroutines. They are referred to this way because they always yield control back to the process that called them rather than to another coroutine.

Generators allow us to perform actions lazily. We can act as and when needed, meaning lazy operations yield output values only when needed. This could be performing a computation, making a connection over a network, or loading data. This lazy evaluation is particularly useful when having to deal with large datasets that may be inefficient or unfeasible. Iterators like range serve a similar purpose, allowing you to lazily produce sequences of values.

It is worth noting that the Rust language is evolving, and one of the areas of development is the async generators. These are special types of generators that can produce values in an async context. Work is ongoing in this area; see the Rust RFC Book site for more details.

Let’s put this theory into practice and write our first simple generator.

Implementing a Simple Generator in Rust

Let’s imagine we want to pull in information from a large data structure contained in a datafile. The datafile is very large, and ideally, we do not want to load it into memory all at once. For our example, we will use a very small datafile of just five rows to demonstrate streaming. Remember, this is an educational example; in the real world, using a generator to read a five-line datafile would be considered overkill! You can make this yourself. We have saved a datafile with five rows, with a number on each row in our project called data.txt.

We need the coroutine features in the previous example, and we import those components:

#![feature(coroutines)]#![feature(coroutine_trait)]usestd::fs::File;usestd::io::{self,BufRead,BufReader};usestd::ops::{Coroutine,CoroutineState};usestd::pin::Pin;

Now let’s create our ReadCoroutine struct:

structReadCoroutine{lines:io::Lines<BufReader<File>>,}implReadCoroutine{fnnew(path:&str)->io::Result<Self>{letfile=File::open(path)?;letreader=BufReader::new(file);letlines=reader.lines();Ok(Self{lines})}}

Then we implement the Coroutine trait for this struct. Our input file contains the numbers 1 to 5, so we are going to be yielding an i32:

implCoroutine<()>forReadCoroutine{typeYield=i32;typeReturn=();fnresume(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,_arg:())->CoroutineState<Self::Yield,Self::Return>{matchself.lines.next(){Some(Ok(line))=>{ifletOk(number)=line.parse::<i32>(){CoroutineState::Yielded(number)}else{CoroutineState::Complete(())}}Some(Err(_))|None=>CoroutineState::Complete(()),}}}

The coroutine contains a Yield statement that allows us to yield a value out of the generator. The coroutine trait has only one required method, which is resume. This allows us to resume execution, picking up at the previous execution point. In our case, the resume method reads lines from the file, parses them into integers, and yields them until no more lines are left to yield, at which point it completes.

Now we will call our function on our test file:

fnmain()->io::Result<()>{letmutcoroutine=ReadCoroutine::new("./data.txt")?;loop{matchPin::new(&mutcoroutine).resume(()){CoroutineState::Yielded(number)=>println!("{:?}",number),CoroutineState::Complete(())=>break,}}Ok(())}

You should get this printout:

12345

Warning

The Coroutine trait was previously known as the Generator trait and GeneratorState, with the name changes taking place in late 2023. If you have an older version of nightly Rust already installed, you will need to update it for the following code to work.

Now we are going to move on to how we can use two coroutines together, with them yielding to each other. This is where you will start to see some of the power of using coroutines.

Stacking Our Coroutines

In this section, we’ll use a file transfer to demonstrate how two coroutines can be used sequentially. This is useful because we might want to transfer a file that is so big, we would not be able to fit all the data into memory. But transferring data bit by bit will enable us to transfer all the data without running out of memory. To enable this solution, one coroutine reads a file and yields values while another coroutine receives values and writes them to a file.

We will reuse our ReadCoroutine and add in our WriteCoroutine from the first section of this chapter. In that example, we wrote 200 thousand random numbers to a file called numbers.txt. Let’s reuse this as the file that we wish to transfer. We will read in numbers.txt and write to a file called output.txt.

We rewrite the WriteCoroutine slightly so it is expecting a path rather than hardcoding it in:

structWriteCoroutine{pubfile_handle:File,}implWriteCoroutine{fnnew(path:&str)->io::Result<Self>{letfile_handle=OpenOptions::new().create(true).append(true).open(path)?;Ok(Self{file_handle})}}

Now we create a manager that has a reader and writer coroutine:

structCoroutineManager{reader:ReadCoroutine,writer:WriteCoroutine}

We need to create a function that sets off our file transfer. First, we will create the new function that instantiates the coroutine manager. This sets read and write filepaths. Second, we will create a new function called run. We need to pin the reader and write in memory so that they can be used throughout the lifetime of the program.

We’ll then create a loop that incorporates both the reader and write functionality. The reader is matched to either Yielded or Complete. If it is Yielded (i.e., there is an output), the writer coroutine takes this in and writes it to the file.

If there are no more numbers left to read, we break the loop. Here is the code:

implCoroutineManager{fnnew(read_path:&str,write_path:&str)->io::Result<Self>{letreader=ReadCoroutine::new(read_path)?;letwriter=WriteCoroutine::new(write_path)?;Ok(Self{reader,writer,})}fnrun(&mutself){letmutread_pin=Pin::new(&mutself.reader);letmutwrite_pin=Pin::new(&mutself.writer);loop{matchread_pin.as_mut().resume(()){CoroutineState::Yielded(number)=>{write_pin.as_mut().resume(number);}CoroutineState::Complete(())=>break,}}}}

We can use this in main:

fnmain(){letmutmanager=CoroutineManager::new("numbers.txt","output.txt").unwrap();manager.run();}

Once you have run this, you can open your new output.txt file to double-check that you have the correct contents.

Let’s recap what we have done here. In essence, we have created a file transfer. One coroutine reads a file line by line and yields its values to another coroutine. This coroutine receives values and writes to the file. In both, the file handles are kept open for the whole execution, which means we don’t have to keep contending with slow I/O. With this type of lazy loading and writing, we can queue up a program to work on processing multiple file transfers, one at a time. Zooming out, you can see the benefit of this approach. We could use this to move 100 large files of multiple gigabytes each from one location to another or even over a network.

Calling a Coroutine from a Coroutine

In the previous example, we used a coroutine to yield a value that was then taken in by the writer coroutine. This process is handled by a manager. In an ideal situation, we would like to remove the need for a manager at all and to allow the coroutines to call each other directly and pass back and forth. These are called symmetric coroutines and are used in other languages. This feature does not come as standard (yet) in Rust, and in order to implement something similar to this, we need to move away from using the Yielded and Complete syntax.

We will create our own trait called SymmetricCoroutine. This has one function, resume_with_input. This takes in an input and provides an output:

traitSymmetricCoroutine{typeInput;typeOutput;fnresume_with_input(self:Pin<&mutSelf>,input:Self::Input)->Self::Output;}

We can now implement this trait for our ReadCoroutine. This outputs values of the type i32. Note we are not using Yielded here anymore but are still using the line parser. This will output the values we need:

implSymmetricCoroutineforReadCoroutine{typeInput=();typeOutput=Option<i32>;fnresume_with_input(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,_input:())->Self::Output{ifletSome(Ok(line))=self.lines.next(){line.parse::<i32>().ok()}else{None}}}

For the WriteCoroutine, we implement this trait as well:

implSymmetricCoroutineforWriteCoroutine{typeInput=i32;typeOutput=();fnresume_with_input(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,input:i32)->Self::Output{writeln!(self.file_handle,"{}",input).unwrap();}}

Finally, we put this together in main:

fnmain()->io::Result<()>{letmutreader=ReadCoroutine::new("numbers.txt")?;letmutwriter=WriteCoroutine::new("output.txt")?;loop{letnumber=Pin::new(&mutreader).resume_with_input(());ifletSome(num)=number{Pin::new(&mutwriter).resume_with_input(num);}else{break;}}Ok(())}

The main function is explicitly instructing how the coroutines should work together. This involves manually scheduling, so technically it does not meet the criteria for truly symmetrical coroutines. We are mimicking some of the functionality of symmetrical coroutines as an educational exercise. A true symmetrical coroutine would pass control from the reader to the writer without having to return to the main function; this is restricted by Rust’s borrowing rules, as both coroutines will need to reference each other. Despite this, it is still a useful example to demonstrate how writing your own coroutines can provide more functionality.

We are now going to move on to looking at async behavior and how we can mimic some of this functionality with simple coroutines.

Mimicking Async Behavior with Coroutines

For this exercise, we need the following imports:

#![feature(coroutines, coroutine_trait)]usestd::{collections::VecDeque,future::Future,ops::{Coroutine,CoroutineState},pin::Pin,task::{Context,Poll},time::Instant,};

In the introduction to this chapter, we discussed how similar coroutines are to async programming, because execution is suspended and later resumed when certain conditions are met. A strong argument could be made that all async programming is a subset of coroutines. Async runtimes are essentially coroutines across threads.

We can demonstrate the pausing of executions with this simple example. First, we set up a coroutine that sleeps for 1 second:

structSleepCoroutine{pubstart:Instant,pubduration:std::time::Duration,}implSleepCoroutine{fnnew(duration:std::time::Duration)->Self{Self{start:Instant::now(),duration,}}}implCoroutine<()>forSleepCoroutine{typeYield=();typeReturn=();fnresume(self:Pin<&mutSelf>,_:())->CoroutineState<Self::Yield,Self::Return>{ifself.start.elapsed()>=self.duration{CoroutineState::Complete(())}else{CoroutineState::Yielded(())}}}

We will set up three instances of SleepCoroutine that will run at the same time. Each instance sleeps for 1 second.

We create a counter and use this to loop through the queue of coroutines—yielding or completing. Finally, we time the whole operation:

fnmain(){letmutsleep_coroutines=VecDeque::new();sleep_coroutines.push_back(SleepCoroutine::new(std::time::Duration::from_secs(1)));sleep_coroutines.push_back(SleepCoroutine::new(std::time::Duration::from_secs(1)));sleep_coroutines.push_back(SleepCoroutine::new(std::time::Duration::from_secs(1)));letmutcounter=0;letstart=Instant::now();whilecounter<sleep_coroutines.len(){letmutcoroutine=sleep_coroutines.pop_front().unwrap();matchPin::new(&mutcoroutine).resume(()){CoroutineState::Yielded(_)=>{sleep_coroutines.push_back(coroutine);},CoroutineState::Complete(_)=>{counter+=1;},}}println!("Took {:?}",start.elapsed());}

This takes 1 second to complete, yet we are carrying out 3 coroutines that each take 1 second to complete. We might therefore expect it to therefore take 3 seconds in total. The shortened amount of time occurs precisely because they are coroutines: they are able to pause their execution and resume at a later time. We are not using Tokio or any other asynchronous runtime. All operations are running in a single thread. They are simply pausing and resuming.

In a way, we have written our own specific executor for this use case. We can even use the executor syntax to make this even clearer. Let’s create an Executor struct that uses VecDeque:

structExecutor{coroutines:VecDeque<Pin<Box<dynCoroutine<(),Yield=(),Return=()>>>>,}

Now we add the basic functionality of Executor:

implExecutor{fnnew()->Self{Self{coroutines:VecDeque::new(),}}}

We define an add function that reuses the same code we had before, where coroutines can be returned to the queue:

fnadd(&mutself,coroutine:Pin<Box<dynCoroutine<(),Yield=(),Return=()>>>){self.coroutines.push_back(coroutine);}

Finally, we wrap our coroutine state code into a function called poll:

fnpoll(&mutself){println!("Polling {} coroutines",self.coroutines.len());letmutcoroutine=self.coroutines.pop_front().unwrap();matchcoroutine.as_mut().resume(()){CoroutineState::Yielded(_)=>{self.coroutines.push_back(coroutine);},CoroutineState::Complete(_)=>{},}}

Our main function can now create the executor, add the coroutines, and then poll them until they are all complete:

fnmain(){letmutexecutor=Executor::new();for_in0..3{letcoroutine=SleepCoroutine::new(std::time::Duration::from_secs(1));executor.add(Box::pin(coroutine));}letstart=Instant::now();while!executor.coroutines.is_empty(){executor.poll();}println!("Took {:?}",start.elapsed());}

That’s it! We have created our first Executor. We will build on this in Chapter 11. Now that we have essentially achieved async functionality from our coroutines and executor, let’s really drive home the relationship between async and coroutines by implementing the Future trait for our SleepCoroutine with the following code:

implFutureforSleepCoroutine{typeOutput=();fnpoll(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{matchPin::new(&mutself).resume(()){CoroutineState::Complete(_)=>Poll::Ready(()),CoroutineState::Yielded(_)=>{cx.waker().wake_by_ref();Poll::Pending},}}}

To recap, this example demonstrates that coroutines pause and resume, similarly to the way async/await works. The difference is that we are using coroutines in a single thread. The major drawback here is that you have to write the coroutine and, if you want, your own executor. This means that they can be highly coupled to the problem you are trying to solve.

In addition to this major drawback, we also lose the benefit of having a pool of threads. Defining your own coroutine may be justified when having the async runtime might be overkill. We also could use coroutines when we want extra control. For instance, we do not really have much control over when an async task is polled in relation to other async tasks when the async task is sent to the runtime. This brings us to our next topic, controlling coroutines.

Controlling Coroutines

Throughout this book, we have controlled the flow of the async task internally. For instance, when we implement the Future trait, we get to choose when to return Pending or Ready, depending on the internal logic of the poll function. The same goes for our async functions; we choose when the async task might yield control back to the executor with the await syntax and choose when the async task returns Ready with return statements.

We can control these async tasks with external Sync primitives such as atomic values and mutexes by getting the async task to react to changes and values in these atomic values and mutexes. However, the logic reacting to external signals has to be coded into the async task before sending the async task to the runtime. For simple cases, this can be fine, but it does expose the async tasks to being brittle if the system around the async task is evolving. This also makes the async task harder to use in other contexts. The async task might also need to know the state of other async tasks before reacting, and this can lead to potential problems such as deadlocks.

Note

A deadlock can happen if task A requires something from task B to progress, and task B requires something from task A to progress, resulting in an impasse. We cover deadlocking, livelocking, and other potential pitfalls with ways to test for them in Chapter 11.

This is where the ease of external control in coroutines can come in handy. To demonstrate how external control can simplify our program, we are going to write a simple program that loops through a vector of coroutines that have a value as well as a status of being alive or dead. When the coroutine gets called, a random number gets generated for the value, and this value is then yielded. We can accumulate all these values and come up with a simple rule of when to kill the coroutine. For the random-number generation, we need this dependency:

[dependencies]rand="0.8.5"

And we need the following imports:

#![feature(coroutines, coroutine_trait)]usestd::{ops::{Coroutine,CoroutineState},pin::Pin,time::Duration,};userand::Rng;

Now we can build a random-number coroutine:

structRandCoRoutine{pubvalue:u8,publive:bool,}implRandCoRoutine{fnnew()->Self{letmutcoroutine=Self{value:0,live:true,};coroutine.generate();coroutine}fngenerate(&mutself){letmutrng=rand::thread_rng();self.value=rng.gen_range(0..=10);}}

Considering that external code is going to be controlling our coroutine, we use a simple generator implementation:

implCoroutine<()>forRandCoRoutine{typeYield=u8;typeReturn=();fnresume(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,_:())->CoroutineState<Self::Yield,Self::Return>{self.generate();CoroutineState::Yielded(self.value)}}

We can use this generator all over the codebase, as it does what is said on the tin. External dependencies are not needed to run our coroutine, and our testing is also simple. In our main function, we create a vector of these coroutines, calling them until all the coroutines in the vector are dead:

letmutcoroutines=Vec::new();for_in0..10{coroutines.push(RandCoRoutine::new());}letmuttotal:u32=0;loop{letmutall_dead=true;formutcoroutineincoroutines.iter_mut(){ifcoroutine.live{...}}ifall_dead{break}}println!("Total: {}",total);

If our coroutine in the loop is alive, we can assume that all the coroutines are not dead, setting the all_dead flag to false. We then call the resume function on the coroutine, extract the result, and come up with a simple rule on whether to kill the coroutine:

all_dead=false;matchPin::new(&mutcoroutine).resume(()){CoroutineState::Yielded(result)=>{total+=resultasu32;},CoroutineState::Complete(_)=>{panic!("Coroutine should not complete");},}ifcoroutine.value<9{coroutine.live=false;}

If we reduce the cutoff for killing the coroutine in the loop, the end total will be higher, as the cutoff is harder to achieve. We are in our main thread, so we have access to everything in that thread. For instance, we could keep track of all dead coroutines and start reanimating coroutines if that number gets too high. We could also use the death number to change the rules of when to kill a coroutine. Now, we could still achieve this toy example in an async task. For instance, a future can hold and poll another future inside it with the following simple example:

structNestingFuture{inner:Pin<Box<dynFuture<Output=()>+Send>>,}implFutureforNestingFuture{typeOutput=();fnpoll(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{matchself.inner.as_mut().poll(cx){Poll::Ready(_)=>Poll::Ready(()),Poll::Pending=>Poll::Pending,}}}

Nothing is stopping NestingFuture from having a vector of other futures that update their own value field every time they are polled and perpetually return Pending as a result. NestingFuture can then extract that value field and come up with rules on whether the recently polled future should be killed. However, NestingFuture would be operating in a thread in the async runtime, resulting in having limited access to data in the main thread.

Considering the ease of control over coroutines, we need to remember that it is not all or nothing. It’s not coroutines versus async. With the following code, we can prove that we can send coroutines over threads:

let(sender,receiver)=std::sync::mpsc::channel::<RandCoRoutine>();let_thread=std::thread::spawn(move||{loop{letmutcoroutine=matchreceiver.recv(){Ok(coroutine)=>coroutine,Err(_)=>break,};matchPin::new(&mutcoroutine).resume(()){CoroutineState::Yielded(result)=>{println!("Coroutine yielded: {}",result);},CoroutineState::Complete(_)=>{panic!("Coroutine should not complete");},}}});std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));sender.send(RandCoRoutine::new()).unwrap();sender.send(RandCoRoutine::new()).unwrap();std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));

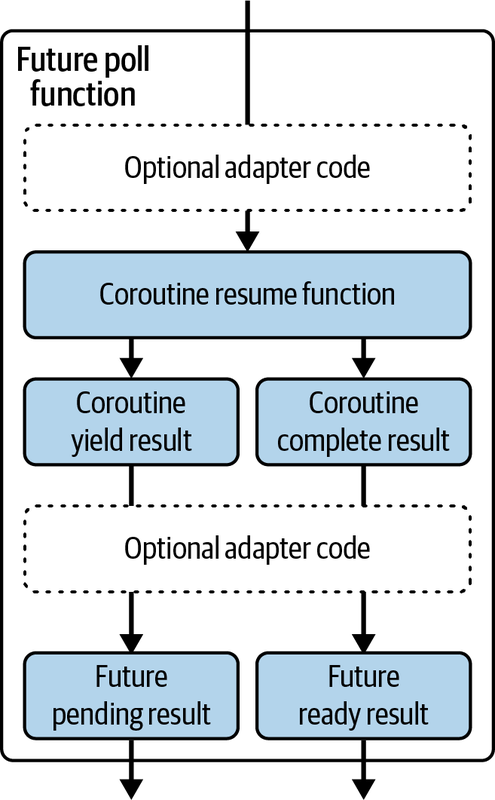

Because coroutines are thread-safe and easily map the results of coroutines, we can finish our journey of understanding coroutines. We can conclude that coroutines are a computational unit that can be paused and resumed. Furthermore, these coroutines also implement Future traits, which can call the resume function and map the results of that function to the results of the poll function, as shown in Figure 5-2.

Figure 5-2. How coroutines can be async adapters

Figure 5-2 also shows that we can slot in optional adapter code between the coroutine functions and the future functions. We can then see coroutines as fundamental computational building blocks. These coroutines can be suspended and resumed in synchronous code and therefore are easy to test in standard testing environments because you do not need an async runtime to test these coroutines. You can also choose when to call the resume function of a coroutine, so testing different orders in which coroutines interact with one another is also simple.

Once you are happy with your coroutine and how it works, you can wrap one or multiple coroutines in a struct that implements the Future trait. This struct is essentially an adapter that enables coroutines to interact with the async runtime. This gives us ultimate flexibility and control over the testing and implementation of our computational processes, and a clear boundary between these computational steps and the async runtime, as the async runtime is basically a thread pool with queues. Anyone who is familiar with unit testing knows that we should not have to communicate with a thread pool to test the computational logic of a function or struct. With this in mind, let’s wrap up our exploration of how coroutines fit in the world of async with testing.

Testing Coroutines

For our testing example, we do not want to excessively bloat the chapter with complex logic, so we will be testing two coroutines that acquire the same mutex and increase the value in the mutex by one. With this, we can test what happens when the lock is acquired and the end result of the lock after the interaction.

Note

While testing using coroutines is simple and powerful, you are not completely on the rocks with regards to testing if you are not using coroutines. Chapter 11 is dedicated to testing, and you will not see a single coroutine in that chapter.

We start with our struct that has a handle to the mutex and a threshold where the coroutine will be complete after the threshold is reached:

usestd::ops::{Coroutine,CoroutineState};usestd::pin::Pin;usestd::sync::{Arc,Mutex};pubstructMutexCoRoutine{pubhandle:Arc<Mutex<u8>>,pubthreshold:u8,}

We then implement the logic behind acquiring the lock and increasing the value by one:

implCoroutine<()>forMutexCoRoutine{typeYield=();typeReturn=();fnresume(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,_:())->CoroutineState<Self::Yield,Self::Return>{matchself.handle.try_lock(){Ok(muthandle)=>{*handle+=1;},Err(_)=>{returnCoroutineState::Yielded(());},}self.threshold-=1;ifself.threshold==0{returnCoroutineState::Complete(())}returnCoroutineState::Yielded(())}}

We are trying to get the lock, but if we cannot, we do not want to block, so we will return a yield. If we get the lock, we increase the value by one, decrease our threshold by one, and then return a Yielded or Complete depending on whether our threshold is reached.

Warning

Blocking code in an async function can cause the entire async runtime to stall because it prevents other tasks from making progress. In Rust, this concept is often referred to as function colors, where functions are either synchronous (blocking) or asynchronous (nonblocking). Mixing these improperly can lead to issues.

For example, if the try_lock method from Mutex were to block, this would be problematic in an async context. While try_lock itself is nonblocking, you should be aware that other locking mechanisms (like lock) would block and thus should be avoided or handled carefully in async functions.

And that’s it; we can test our coroutine in the same file with the following template:

#[cfg(test)]modtests{usesuper::*;usestd::future::Future;usestd::task::{Context,Poll};usestd::time::Duration;// sync testing interfacefncheck_yield(coroutine:&mutMutexCoRoutine)->bool{...}// async runtime interfaceimplFutureforMutexCoRoutine{...}#[test]fnbasic_test(){...}#[tokio::test]asyncfnasync_test(){...}}

Here we are going to check how our code works directly and then how our code runs in an async runtime. We have two interfaces. We do not want to have to alter our code to satisfy tests. Instead, we have a simple interface that returns a bool based on the type returned by our coroutine; here’s the function definition:

fncheck_yield(coroutine:&mutMutexCoRoutine)->bool{matchPin::new(coroutine).resume(()){CoroutineState::Yielded(_)=>{true},CoroutineState::Complete(_)=>{false},}}

With our async interface, we simply map the coroutine outputs to the equivalent async outputs:

implFutureforMutexCoRoutine{typeOutput=();fnpoll(mutself:Pin<&mutSelf>,cx:&mutContext<'_>)->Poll<Self::Output>{matchPin::new(&mutself).resume(()){CoroutineState::Complete(_)=>Poll::Ready(()),CoroutineState::Yielded(_)=>{cx.waker().wake_by_ref();Poll::Pending},}}}

We are now ready to build our first basic test in the basic_test function. We initially define the mutex and coroutines:

lethandle=Arc::new(Mutex::new(0));letmutfirst_coroutine=MutexCoRoutine{handle:handle.clone(),threshold:2,};letmutsecond_coroutine=MutexCoRoutine{handle:handle.clone(),threshold:2,};

We first want to acquire the lock ourselves and then call both coroutines, checking that they return a yield and that the value of the mutex is still zero because we have lock:

letlock=handle.lock().unwrap();for_in0..3{assert_eq!(check_yield(&mutfirst_coroutine),true);assert_eq!(check_yield(&mutsecond_coroutine),true);}assert_eq!(*lock,0);std::mem::drop(lock);

Note

You may have noticed that we drop the lock after the initial testing of the first two yields. If we do not do this, the rest of the tests will fail, as our coroutines will never be able to acquire the lock.

We execute the loop to prove that the threshold is also not being altered when the coroutine fails to get the lock. If the threshold had been altered, after two iterations the coroutine would have returned a complete, and the next call to the coroutine would have resulted in an error. While the test would have picked this up without the loop, having the loop at the start removes any confusion as to what is causing the break in the test.

After we drop the lock, we call the coroutines twice each to ensure that they return what we expect and check on the mutex between all the calls to ensure that the state is changing in the exact way we want it:

assert_eq!(check_yield(&mutfirst_coroutine),true);assert_eq!(*handle.lock().unwrap(),1);assert_eq!(check_yield(&mutsecond_coroutine),true);assert_eq!(*handle.lock().unwrap(),2);assert_eq!(check_yield(&mutfirst_coroutine),false);assert_eq!(*handle.lock().unwrap(),3);assert_eq!(check_yield(&mutsecond_coroutine),false);assert_eq!(*handle.lock().unwrap(),4);

And our first test is complete.

In our async test, we create the mutex and coroutines in the exact same way. However, we are now testing that our behavior end result is the same in an async runtime and that our async interface is working the way we expect. Because we are using the Tokio testing feature, we can just spawn our tasks, wait on them, and inspect the lock:

lethandle_one=tokio::spawn(asyncmove{first_coroutine.await;});lethandle_two=tokio::spawn(asyncmove{second_coroutine.await;});handle_one.await.unwrap();handle_two.await.unwrap();assert_eq!(*handle.lock().unwrap(),4);

If we run the command cargo test, we will see that both of our tests work. And there we have it! We have inspected the interaction between two coroutines and a mutex step by step, inspecting the state between each iteration. Our coroutines work in synchronous code. But, with a simple adapter, we can also see that our coroutines work in an async runtime exactly the way we expect them to! We can see that we do not have the ability to inspect the mutex at each interaction of a coroutine with the async test. The async executor is doing its own thing.

Summary

In this chapter, we built our own coroutines by implementing the Coroutinse trait and used Yield and Complete to pause and resume our coroutine. We implemented a pipeline in which a file can be read by one coroutine that yields values and those values can be used by a second coroutine and written to a file. Finally, we built our own executor and saw how coroutines are truly pausing and resuming.

As you worked through the chapter, you were likely struck by the similarities between Yield/Complete in coroutines and Pending/Ready in async. In our opinion, the best way to view this is that async/await is a subtype of a coroutine. It is a coroutine that operates across threads and uses queues. You can suspend an activity and come back to it in both coroutines and async programming.

Coroutines enable us to structure our code, because they can act as the seam between async and synchronous code. With coroutines, we can build synchronous code modules and then evaluate them by using standard tests. We can build adapters that are coroutines so that our synchronous code can connect with code that needs async functionality, but that async functionality is represented as coroutines. Then, we can unit-test our coroutines to see how they behave when they are polled in various orders and combinations. We can inject those coroutines into Future trait implementations to integrate our code into an async runtime, because we can call our coroutines in the future’s poll function. Here, we just need to keep this async code isolated with interfaces. One async function can call your code and then pass outputs into the third-party async code, and vice versa.

A good way of isolating code is with reactive programming, where our units of code can consume data though subscriptions to broadcast channels. We explore this in Chapter 6.