Chapter 8. The Actor Model

Actors are isolated pieces of code that communicate exclusively through message passing. Actors can also have state that they can reference and manipulate. Because we have async-compatible nonblocking channels, our async runtime can juggle multiple actors, progressing these actors only when they receive a message in their channel.

The isolation of actors enables easy async testing and simple implementation of async systems. By the end of this chapter, you will be able to build an actor system that has a router actor. This actor system you build can easily be called anywhere in your program without having to pass a reference around for your actor system. You will also be able to build a supervisor heartbeat system that will keep track of other actors and force a restart of those actors if they fail to ping the supervisor past a time threshold. To start on this journey, you need to understand how to build basic actors.

Building a Basic Actor

The most basic actor we can build is an async function that is stuck in an infinite loop listening for messages:

usetokio::sync::{mpsc::channel,mpsc::{Receiver,Sender},oneshot};structMessage{value:i64}asyncfnbasic_actor(mutrx:Receiver<Message>){letmutstate=0;whileletSome(msg)=rx.recv().await{state+=msg.value;println!("Received: {}",msg.value);println!("State: {}",state);}}

The actor listens to incoming messages by using a multiproducer, single-consumer channel (mpsc), updates the state, and then prints it out. We can test our actor as follows:

#[tokio::main]asyncfnmain(){let(tx,rx)=channel::<Message>(100);let_actor_handle=tokio::spawn(basic_actor(rx));foriin0..10{letmsg=Message{value:i};tx.send(msg).await.unwrap();}}

But what if we want to receive a response? Right now, we are sending a message into the void and looking at the printout in the terminal. We can facilitate a response by packaging oneshot::Sender in the message that we are sending to the actor. The receiving actor can then use that oneshot::Sender to send a response. We can define our responding actor with the following code:

structRespMessage{value:i32,responder:oneshot::Sender<i64>}asyncfnresp_actor(mutrx:Receiver<RespMessage>){letmutstate=0;whileletSome(msg)=rx.recv().await{state+=msg.value;ifmsg.responder.send(state).is_err(){eprintln!("Failed to send response");}}}

If we wanted to send a message to our responding actor, we would have to construct a oneshot channel, use it to construct a message, send over the message, and then wait for the response. The following code depicts a basic example of how to achieve this:

let(tx,rx)=channel::<RespMessage>(100);let_resp_actor_handle=tokio::spawn(async{resp_actor(rx).await;});foriin0..10{let(resp_tx,resp_rx)=oneshot::channel::<i64>();letmsg=RespMessage{value:i,responder:resp_tx};tx.send(msg).await.unwrap();println!("Response: {}",resp_rx.await.unwrap());}

Here, we are using a oneshot channel because we need the response to be sent only once, and then the client code can go about doing other things. This is the best choice for our use case because oneshot channels are optimized in terms of memory and synchronization for the use case of sending just one message back and then closing.

Considering that we are sending structs over the channel to our actor, you can see that our functionality can increase in complexity. For instance, sending an enum that encapsulates multiple messages could instruct the actor to do a range of actions based on the type of message being sent. Actors can also create new actors or send messages to other actors.

From the example we have shown, we could just use a mutex and acquire it for the mutation of the state. The mutex would be simple to code, but how would it match up to the actor?

Working with Actors Versus Mutexes

For this exercise, we need these additional imports:

usestd::sync::Arc;usetokio::sync::Mutex;usetokio::sync::mpsc::error::TryRecvError;

To re-create what our actor in the previous section did with a mutex, we have a function that takes the following form:

asyncfnactor_replacement(state:Arc<Mutex<i64>>,value:i64)->i64{letmutstate=state.lock().await;*state+=value;return*state}

While this is simple to write, how does this measure up in terms of performance? We can devise a simple test:

letstate=Arc::new(Mutex::new(0));letmuthandles=Vec::new();letnow=tokio::time::Instant::now();foriin0..100000000{letstate_ref=state.clone();letfuture=asyncmove{lethandle=tokio::spawn(asyncmove{actor_replacement(state_ref,i).await});let_=handle.await.unwrap();};handles.push(tokio::spawn(future));}forhandleinhandles{let_=handle.await.unwrap();}println!("Elapsed: {:?}",now.elapsed());

We have spawned a lot of tasks at once, trying to gain access to the mutex, and then waited on them. If we spawned one task at a time, we would not get the true effect that the concurrency of our mutex has on the outcome. Instead, we would just be getting the speed of individual transactions. We are running a large number of tasks because we want to see a statistically significant difference between the approaches.

These tests take a long time to run, but the results cannot be misinterpreted. At the time of this writing on an M2 MacBook with high specs, the time taken for all the mutex tasks to complete is 155 seconds when running the code in --release mode.

To run the same test using our actor in the previous section, we need this code:

let(tx,rx)=channel::<RespMessage>(100000000);let_resp_actor_handle=tokio::spawn(async{resp_actor(rx).await;});letmuthandles=Vec::new();letnow=tokio::time::Instant::now();foriin0..100000000{lettx_ref=tx.clone();letfuture=asyncmove{let(resp_tx,resp_rx)=oneshot::channel::<i64>();letmsg=RespMessage{value:i,responder:resp_tx};tx_ref.send(msg).await.unwrap();let_=resp_rx.await.unwrap();};handles.push(tokio::spawn(future));}forhandleinhandles{let_=handle.await.unwrap();}println!("Elapsed: {:?}",now.elapsed());

Running this test takes 103 seconds at the time of this writing. Note that we ran the tests in --release mode to see what the compiler optimizations would do to the system. The actor is faster by 52 seconds. One reason is the overhead of acquiring the mutex. When placing a message in a channel, we have to check whether the channel is full or has been closed. When acquiring a mutex, the checks are more complicated. These checks typically involve checking whether the lock is held by another task. If it is, the task trying to acquire the lock then needs to register interest and wait to be notified.

Note

Generally, passing messages through channels can scale better than mutexes in concurrent environments because the senders do not have to wait for other tasks to finish what they are doing. They may have to wait to put a message on the queue of the channel, but waiting for a message to be put on a queue is quicker than waiting for an operation to finish what it is doing with the mutex, yield the lock, and then for the awaiting task to acquire the lock. As a result, channels can result in higher throughput.

To drive our point home, let’s explore a scenario in which the transaction is more complex than just increasing the value by one. Maybe we have a few checks and a calculation before committing the final result to the state and returning the number. As efficient engineers, we may want to do other things while that process is happening. Because we are sending a message and waiting for the response, we already have that luxury with our actor code, as you can see here:

letfuture=asyncmove{let(resp_tx,resp_rx)=oneshot::channel::<i32>();letmsg=RespMessage{value:i,responder:resp_tx};tx_ref.send(msg).await.unwrap();// do something elselet_=resp_rx.await.unwrap();};

However, our mutex implementation would merely yield the control back to the scheduler. If we wanted to progress our mutex task while waiting for the complex transaction to complete, we would have to spawn another async task as follows:

asyncfnactor_replacement(state:Arc<Mutex<i32>>,value:i32)->i32{letupdate_handle=tokio::spawn(asyncmove{letmutstate=state.lock().await;*state+=value;return*state});// do something elseupdate_handle.await.unwrap()}

However, the overhead of spawning those extra async tasks shoots up the time elapsed in our test to 174 seconds. That is 73 seconds more than the actor for the same functionality. This is not surprising, as we are sending an async task to the runtime and getting a handle back just to allow us to progress a wait for our transaction result later in our task.

With our test results in mind, you can see why we would want to use actors. Actors are more complex to write. You need to pass messages over a channel and package a oneshot channel for the actor to respond just to get the result. This is more complex than acquiring a lock. However, the flexibility of choosing when to wait for the result of that message comes for free with actors. Mutexes, on the other hand, have a big penalty if that flexibility is desired.

We can also argue that actors are easier to conceptualize. If we think about this, actors contain their state. If you want to see all interactions with that state, you look in the actor code. However, with mutex codebases, we do not know where all the interactions with the state are. The distributed interactions with the mutex also increase the risk of it being highly coupled throughout the system, making refactoring a headache.

Now that we have gotten our actors working, we need to be able to utilize them in our system. The easiest way to implement actors into the system with a minimal footprint is the router pattern.

Implementing the Router Pattern

For our routing, we construct a router actor that accepts messages. These messages can be wrapped in enums to help our router locate the correct actor. For our example, we are going to implement a basic key-value store. We must stress that although we are building the key-value store in Rust, you should not use this educational example in production. Established solutions like RocksDB and Redis have put a lot of work and expertise into making their key-value stores robust and scalable.

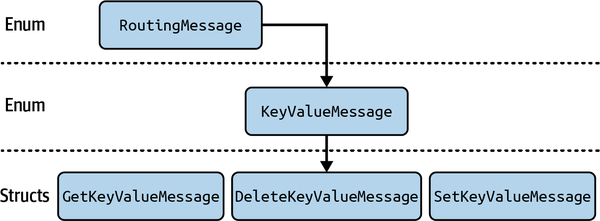

For our key-value store, we need to set, get, and delete keys. We can signal all these operations with the message layout defined in Figure 8-1.

Figure 8-1. The enum structure of the router actor message

Before we code anything, we need the imports defined here:

usetokio::sync::{mpsc::channel,mpsc::{Receiver,Sender},oneshot,};usestd::sync::OnceLock;

We also need to define our message layout shown in Figure 8-1:

structSetKeyValueMessage{key:String,value:Vec<u8>,response:oneshot::Sender<()>,}structGetKeyValueMessage{key:String,response:oneshot::Sender<Option<Vec<u8>>>,}structDeleteKeyValueMessage{key:String,response:oneshot::Sender<()>,}enumKeyValueMessage{Get(GetKeyValueMessage),Delete(DeleteKeyValueMessage),Set(SetKeyValueMessage),}enumRoutingMessage{KeyValue(KeyValueMessage),}

We now have a message that can be routed to the key-value actor, and this message signals the correct operation with the data needed to perform the operation. For our key-value actor, we accept the KeyValueMessage, match the variant, and perform the operation as follows:

asyncfnkey_value_actor(mutreceiver:Receiver<KeyValueMessage>){letmutmap=std::collections::HashMap::new();whileletSome(message)=receiver.recv().await{matchmessage{KeyValueMessage::Get(GetKeyValueMessage{key,response})=>{let_=response.send(map.get(&key).cloned());}KeyValueMessage::Delete(DeleteKeyValueMessage{key,response})=>{map.remove(&key);let_=response.send(());}KeyValueMessage::Set(SetKeyValueMessage{key,value,response})=>{map.insert(key,value);let_=response.send(());}}}}

With our handling of the key-value message, we need to connect our key-value actor with a router actor:

asyncfnrouter(mutreceiver:Receiver<RoutingMessage>){let(key_value_sender,key_value_receiver)=channel(32);tokio::spawn(key_value_actor(key_value_receiver));whileletSome(message)=receiver.recv().await{matchmessage{RoutingMessage::KeyValue(message)=>{let_=key_value_sender.send(message).await;}}}}

We create the key-value actor in our router actor. Actors can create other actors. Putting the creation of the key-value actor in the router actor ensures that there will never be a mistake in setting up the system. It also reduces the footprint of our actor system’s setup in our program. Our router is our interface, so everything will go through the router to get to the other actors.

Now that the router is defined, we must turn our attention to the channel for that router. All the messages being sent into our actor system will go through that channel. We have chosen the number 32 arbitrarily; this means that the channel can hold up to 32 messages at a time. This buffer size gives us some flexibility.

The system would not be very useful if we had to keep track of references to the sender of that channel. If a developer wants to send a message to our actor system and they are four levels deep, imagine the frustration that developer will feel if they have to trace the function they are using back to main, opening up a parameter for the channel sender for each function leading to the function that they are working on. Making changes later would be equally frustrating. To avoid such frustrations, we define the sender as a global static:

staticROUTER_SENDER:OnceLock<Sender<RoutingMessage>>=OnceLock::new();

When we create the main channel for the router, we will set the sender. You might be wondering whether it would be more ergonomic to construct the main channel and set ROUTER_SENDER inside the router actor function. However, you could get some concurrency issues if functions try to send messages down the main channel before the channel is set. Remember, async runtimes can span multiple threads, so it’s possible that an async task could be trying to call the channel while the router actor is trying to set up the channel. Therefore, it is better to set up the channel at the start of the main function before spawning anything. Then, even if the router actor is not the first task to be polled on the async runtime, it can still access the messages sent to the channel before it was polled.

Our router actor is now ready to receive messages and route them to our key-value store. We need some functions that enable us to send key-value messages. We can start with our set function, which is defined by the following code:

pubasyncfnset(key:String,value:Vec<u8>)->Result<(),std::io::Error>{let(tx,rx)=oneshot::channel();ROUTER_SENDER.get().unwrap().send(RoutingMessage::KeyValue(KeyValueMessage::Set(SetKeyValueMessage{key,value,response:tx,}))).await.unwrap();rx.await.unwrap();Ok(())}

This code has a fair number of unwraps, but if our system is failing because of channel errors, we have bigger problems. These unwraps merely avoid code bloat in the chapter. We cover handling errors later in “Creating Actor Supervision”. We can see that our routing message is self-explanatory. We know it is a routing message and that the message is routed to the key-value actor. We then know which method we are calling in the key-value actor and the data being passed in. The routing message enums are just enough information to tell us the route intended for the function.

Now that our set function is defined, you can probably build the get function by yourself. Give that a try.

Hopefully, your get function goes along the same lines as this:

pubasyncfnget(key:String)->Result<Option<Vec<u8>>,std::io::Error>{let(tx,rx)=oneshot::channel();ROUTER_SENDER.get().unwrap().send(RoutingMessage::KeyValue(KeyValueMessage::Get(GetKeyValueMessage{key,response:tx,}))).await.unwrap();Ok(rx.await.unwrap())}

Our delete function is pretty much identical to get, apart from the different route and the fact that the delete function does not return anything:

pubasyncfndelete(key:String)->Result<(),std::io::Error>{let(tx,rx)=oneshot::channel();ROUTER_SENDER.get().unwrap().send(RoutingMessage::KeyValue(KeyValueMessage::Delete(DeleteKeyValueMessage{key,response:tx,}))).await.unwrap();rx.await.unwrap();Ok(())}

And our system is ready. We can test our router and key-value store with the main function:

#[tokio::main]asyncfnmain()->Result<(),std::io::Error>{let(sender,receiver)=channel(32);ROUTER_SENDER.set(sender).unwrap();tokio::spawn(router(receiver));let_=set("hello".to_owned(),b"world".to_vec()).await?;letvalue=get("hello".to_owned()).await?;println!("value: {:?}",String::from_utf8(value.unwrap()));let_=delete("hello".to_owned()).await?;letvalue=get("hello".to_owned()).await?;println!("value: {:?}",value);Ok(())}

The code gives us the following printout:

value: Ok("world")

value: None

Our key-value store is working and operational. However, what happens when our system closes down or crashes? We need an actor that can keep track of the state and recover it when restarting the system.

Implementing State Recovery for Actors

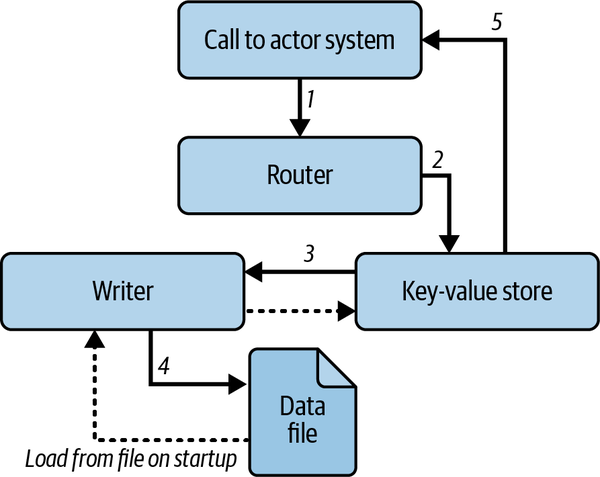

Right now our system has a key-value store actor. However, our system might be stopped and started again, or an actor could crash. If this happens, we could lose all our data, which is not good. To reduce the risk of data loss, we will create another actor that writes our data to a file. The outline of our new system is defined in Figure 8-2.

Figure 8-2. A writer backup actor system

From Figure 8-2, we can see the following steps that are carried out:

-

A call is made to our actor system.

-

The router sends the message to the key-value store actor.

-

Our key-value store actor clones the operation and sends that operation to the writer actor.

-

The writer actor performs the operation on its own map and writes the map to the datafile.

-

The key-value store performs the operation on its own map and returns the result to the code that called the actor system.

When our actor system starts up, we will have this sequence:

-

Our router actor starts, creating our key-value store actor.

-

Our key-value store actor creates our write actor.

-

When our writer actor starts, it reads the data from the file, populates itself, and also sends the data to the key-value store actor.

Note

We have given our writer actor exclusive access to the datafile. This will avoid concurrency issues because the writer actor can process only one transaction at a time, and no other resources will be altering the file. The writer’s exclusivity to the file can also give us performance gains because the writer actor can keep the file handle to the datafile open for the entire duration of its lifetime instead of opening the file for each write. This drastically reduces the number of calls to the OS for permissions and checks for file availability.

For this system, we need to update the initialization code for the key-value actor. We also need to build the writer actor and add a new message for the writer actor that can be constructed from the key-value message.

Before we write any new code, we need the following imports:

useserde_json;usetokio::fs::File;usetokio::io::{self,AsyncReadExt,AsyncWriteExt,AsyncSeekExt};usestd::collections::HashMap;

For our writer message, we need the writer to set and delete values. However, we also need our writer to return the full state that has been read from the file, giving us the following definition:

enumWriterLogMessage{Set(String,Vec<u8>),Delete(String),Get(oneshot::Sender<HashMap<String,Vec<u8>>>),}

We need to construct this message from the key-value message without consuming it:

implWriterLogMessage{fnfrom_key_value_message(message:&KeyValueMessage)->Option<WriterLogMessage>{matchmessage{KeyValueMessage::Get(_)=>None,KeyValueMessage::Delete(message)=>Some(WriterLogMessage::Delete(message.key.clone())),KeyValueMessage::Set(message)=>Some(WriterLogMessage::Set(message.key.clone(),message.value.clone())),}}}

Our message definitions are now complete. We need only one more piece of functionality before we can write our writer actor: the loading of the state. We need both actors to load the state on startup, so our file loading is defined by the following isolated function:

asyncfnread_data_from_file(file_path:&str)->io::Result<HashMap<String,Vec<u8>>>{letmutfile=File::open(file_path).await?;letmutcontents=String::new();file.read_to_string(&mutcontents).await?;letdata:HashMap<String,Vec<u8>>=serde_json::from_str(&contents)?;Ok(data)}

Although this works, we need the loading of the state to be fault-tolerant. It is nice to recover the state of the actors before they were shut down, but our system wouldn’t be very good if our actors failed to run at all because they could not load from a missing or corrupted state file. Therefore, we wrap our loading in a function that will return an empty hashmap if a problem occurs when loading the state:

asyncfnload_map(file_path:&str)->HashMap<String,Vec<u8>>{matchread_data_from_file(file_path).await{Ok(data)=>{println!("Data loaded from file: {:?}",data);returndata},Err(e)=>{println!("Failed to read from file: {:?}",e);println!("Starting with an empty hashmap.");returnHashMap::new()}}}

We print this out so we can check the logs of the system if we are not getting the results we expect.

We are now ready to build our writer actor. Our writer actor needs to load data from the file and then listen to incoming messages:

asyncfnwriter_actor(mutreceiver:Receiver<WriterLogMessage>)->io::Result<()>{letmutmap=load_map("./data.json").await;letmutfile=File::create("./data.json").await.unwrap();whileletSome(message)=receiver.recv().await{matchmessage{...}letcontents=serde_json::to_string(&map).unwrap();file.set_len(0).await?;file.seek(std::io::SeekFrom::Start(0)).await?;file.write_all(contents.as_bytes()).await?;file.flush().await?;}Ok(())}

Note

You can see that we wipe the file and write the entire map between each message cycle. This is not an efficient way of writing to the file. However, this chapter is focused on actors and how to use them. Trade-offs around writing transactions to files is a big subject involving various file types, batch writing, and garbage collection to clean up data. If this interests you, Database Internals by Alex Petrov (O’Reilly, 2019) provides comprehensive coverage on writing transactions to files.

Inside our matching of the message in the writer actor, we insert, remove, or clone and then return the entire map:

matchmessage{WriterLogMessage::Set(key,value)=>{map.insert(key,value);}WriterLogMessage::Delete(key)=>{map.remove(&key);},WriterLogMessage::Get(response)=>{let_=response.send(map.clone());}}

While our router actor remains untouched, our key-value actor needs to create the writer actor before it does anything else:

let(writer_key_value_sender,writer_key_value_receiver)=channel(32);tokio::spawn(writer_actor(writer_key_value_receiver));

Our key-value actor then needs to get the state of the map from our writer actor:

let(get_sender,get_receiver)=oneshot::channel();let_=writer_key_value_sender.send(WriterLogMessage::Get(get_sender)).await;letmutmap=get_receiver.await.unwrap();

Finally, the key-value actor can construct a writer message and send that message to the writer actor before handling the transaction itself:

whileletSome(message)=receiver.recv().await{ifletSome(write_message)=WriterLogMessage::from_key_value_message(&message){let_=writer_key_value_sender.send(write_message).await;}matchmessage{...}}

And with this, our system supports writing and loading from a file while all the key-value transactions are handled in memory. If you play around with your code in the main function, commenting bits out and inspecting the data.json file, you will see that it works. However, if your system is running on something like a server, you may not be manually monitoring the file to see what is going on. Now that our actor system has gotten more complex, our writer actor could have crashed and not be running, but we would be none the wiser because our key-value actor could still be running. This is where supervision comes in, as we need to keep track of the state of our actors.

Creating Actor Supervision

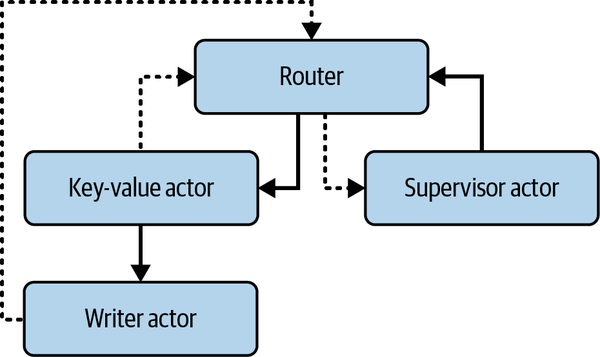

Right now we have two actors: the writer and key-value store actors. In this section, we are going to build a supervisor actor that keeps track of every actor in our system. This is where we’ll be grateful that we have implemented the router pattern. Creating a supervisor actor and then passing the sender of the supervisor actor channel through to every actor would be a headache. Instead, we can send update messages to the supervisor actor through the router, as every actor has direct access to ROUTER_SENDER. The supervisor can also send reset requests to the correct actor through the browser, as depicted in Figure 8-3.

You can see in Figure 8-3 that if we do not get an update from either the key-value actor or the writer actor, we can reset the key-value actor. Because we can get the key-value actor to hold the handle of the writer actor when the key-value actor creates the writer actor, the writer actor will die if the key-value actor dies. When the key-value actor is created again, the writer actor will also be created.

Figure 8-3. A supervisor actor system

To achieve this heartbeat supervisor mechanism, we must refactor our actors a bit, but this will illustrate how a little trade-off in complexity enables us to keep track of and manage our long-running actors. Before we code anything, however, we do need the following import to handle the time checks for our actors:

usetokio::time::{self,Duration,Instant};

We also need to support the resetting of actors and registering of heartbeats. Therefore, we must expand our RoutingMessage:

enumRoutingMessage{KeyValue(KeyValueMessage),Heartbeat(ActorType),Reset(ActorType),}#[derive(Clone, Copy, PartialEq, Eq, Hash, Debug)]enumActorType{KeyValue,Writer}

Here, we can request a reset or register a heartbeat of any actor that we want to declare in the ActorType enum.

Our first refactor can be our key-value actor. First, we define a handle for the writer actor:

let(writer_key_value_sender,writer_key_value_receiver)=channel(32);let_writer_handle=tokio::spawn(writer_actor(writer_key_value_receiver));

We still send a get message to the writer actor to populate the map, but then we lift our message-handling code into an infinite loop so we can implement a timeout:

lettimeout_duration=Duration::from_millis(200);letrouter_sender=ROUTER_SENDER.get().unwrap().clone();loop{matchtime::timeout(timeout_duration,receiver.recv()).await{Ok(Some(message))=>{ifletSome(write_message)=WriterLogMessage::from_key_value_message(&message){let_=writer_key_value_sender.send(write_message).await;}matchmessage{...}},Ok(None)=>break,Err(_)=>{router_sender.send(RoutingMessage::Heartbeat(ActorType::KeyValue)).await.unwrap();}};}

At the end of the cycle, we send a heartbeat message to the router to say that our key-value store is still alive. We also have a timeout, so if 200 ms passes, we still run a cycle because we do not want the lack of incoming messages to be the reason our supervisor thinks that our actor is dead or stuck.

We need a similar approach for our writer actor. We encourage you to try to code this yourself. Hopefully, your attempt will be similar to the following code:

lettimeout_duration=Duration::from_millis(200);letrouter_sender=ROUTER_SENDER.get().unwrap().clone();loop{matchtime::timeout(timeout_duration,receiver.recv()).await{Ok(Some(message))=>{matchmessage{...}letcontents=serde_json::to_string(&map).unwrap();file.set_len(0).await?;file.seek(std::io::SeekFrom::Start(0)).await?;file.write_all(contents.as_bytes()).await?;file.flush().await?;},Ok(None)=>break,Err(_)=>{router_sender.send(RoutingMessage::Heartbeat(ActorType::Writer)).await.unwrap();}};}

Our actors now support sending heartbeats to the router for the supervisor to keep track of. Next we need to build our supervisor actor. Our supervisor actor has a similar approach to the rest of the actors. It has an infinite loop containing a timeout because the lack of heartbeat messages should not stop the supervisor actor from checking on the state of the actors it is tracking. In fact, the lack of heartbeat messages would suggest that the system is in need of checking. However, instead of sending a message at the end of the infinite loop cycle, the supervisor actor loops through its own state to check for any actors that have not checked in. If the actor is out of date, the supervisor actor sends a reset request to the router. The outline of this process is laid out in the following code:

asyncfnheartbeat_actor(mutreceiver:Receiver<ActorType>){letmutmap=HashMap::new();lettimeout_duration=Duration::from_millis(200);loop{matchtime::timeout(timeout_duration,receiver.recv()).await{Ok(Some(actor_name))=>map.insert(actor_name,Instant::now()),Ok(None)=>break,Err(_)=>{continue;}};lethalf_second_ago=Instant::now()-Duration::from_millis(500);for(key,&value)inmap.iter(){...}}}

We have decided that we are going to have a cutoff of half a second. The smaller the cutoff, the quicker the actor is restarted after failure. However, this increases work as the timeouts in the actors waiting for messages also have to be smaller to keep the supervisor satisfied.

When we are looping through our state keys to check the actors, we send a request for a reset if the cutoff is exceeded:

ifvalue<half_second_ago{matchkey{ActorType::KeyValue|ActorType::Writer=>{ROUTER_SENDER.get().unwrap().send(RoutingMessage::Reset(ActorType::KeyValue)).await.unwrap();map.remove(&ActorType::KeyValue);map.remove(&ActorType::Writer);break;}}}

You might notice that we reset the key-value actor even if the writer actor is failing. This is because the key-value actor will restart the writer actor. We also remove the keys from the map because when the key-value actor starts again, it will send a heartbeat message causing the keys to be checked again. However, the writer key might still be out of date, causing a second unnecessary fire. We can start checking those actors after they have registered again.

Our router actor now must support all our changes. First of all, we need to set our key-value channel and handle to be mutable:

let(mutkey_value_sender,mutkey_value_receiver)=channel(32);letmutkey_value_handle=tokio::spawn(key_value_actor(key_value_receiver));

This is because we need to reallocate a new handle and channel if the key-value actor is reset. We then spawn the heartbeat actor to supervise our other actors:

let(heartbeat_sender,heartbeat_receiver)=channel(32);tokio::spawn(heartbeat_actor(heartbeat_receiver));

Now that our actor system is running, our router actor can handle incoming messages:

whileletSome(message)=receiver.recv().await{matchmessage{RoutingMessage::KeyValue(message)=>{let_=key_value_sender.send(message).await;},RoutingMessage::Heartbeat(message)=>{let_=heartbeat_sender.send(message).await;},RoutingMessage::Reset(message)=>{...}}}

For our reset, we must carry out a couple of steps. First, we create a new channel. We abort the key-value actor, reallocate the sender and receiver to the new channel, and then spawn a new key-value actor:

matchmessage{ActorType::KeyValue|ActorType::Writer=>{let(new_key_value_sender,new_key_value_receiver)=channel(32);key_value_handle.abort();key_value_sender=new_key_value_sender;key_value_receiver=new_key_value_receiver;key_value_handle=tokio::spawn(key_value_actor(key_value_receiver));time::sleep(Duration::from_millis(100)).await;},}

You can see that we have a small sleep to ensure that the task has spawned and is running on the async runtime. You may worry that more requests to the key-value actor might be being sent during this transition, which may error. However, all requests go through the router actor. If these messages are being sent to the router for the key-value actor, they will just queue up in the channel of the router. With this, you can see how actor systems are very fault-tolerant.

Since this code has a lot of moving parts, let’s run this all together with the main function:

Warning

Before you run the following code, make sure that your data.json file has a set of empty curly braces like the following:

{}

#[tokio::main]asyncfnmain()->Result<(),std::io::Error>{let(sender,receiver)=channel(32);ROUTER_SENDER.set(sender).unwrap();tokio::spawn(router(receiver));let_=set("hello".to_string(),b"world".to_vec()).await?;letvalue=get("hello".to_string()).await?;println!("value: {:?}",value);letvalue=get("hello".to_string()).await?;println!("value: {:?}",value);ROUTER_SENDER.get().unwrap().send(RoutingMessage::Reset(ActorType::KeyValue)).await.unwrap();letvalue=get("hello".to_string()).await?;println!("value: {:?}",value);let_=set("test".to_string(),b"world".to_vec()).await?;std::thread::sleep(std::time::Duration::from_secs(1));Ok(())}

Running our main gives us this printout:

Data loaded from file: {}

value: Some([119, 111, 114, 108, 100])

value: Some([119, 111, 114, 108, 100])

Data loaded from file: {"hello": [119, 111, 114, 108, 100]}

value: Some([119, 111, 114, 108, 100])

We can see that the data was loaded by the writer actor initially when setting up the system. Our get functions work after the setting of the hello value. We then manually forced a reset. Here we can see that the data is loaded again, meaning that the writer actor is being restarted. We know that the previous writer actor died because the writer actor gets the file handle and keeps hold of it. We would get an error as the file descriptor would already be held.

If you want to sleep soundly at night, you can add a timestamp before the loop of the writer actor and print out the timestamp at the start of every iteration of the loop so the printout of the timestamp is not dependent on any incoming messages. This would give a printout like the following:

Data loaded from file: {}

writer instance: Instant { tv_sec: 1627237, tv_nsec: 669830291 }

value: Some([119, 111, 114, 108, 100])

writer instance: Instant { tv_sec: 1627237, tv_nsec: 669830291 }

value: Some([119, 111, 114, 108, 100])

Starting key_value_actor

writer instance: Instant { tv_sec: 1627237, tv_nsec: 669830291 }

Data loaded from file: {"hello": [119, 111, 114, 108, 100]}

writer instance: Instant { tv_sec: 1627237, tv_nsec: 773026500 }

value: Some([119, 111, 114, 108, 100])

writer instance: Instant { tv_sec: 1627237, tv_nsec: 773026500 }

writer instance: Instant { tv_sec: 1627237, tv_nsec: 773026500 }

writer instance: Instant { tv_sec: 1627237, tv_nsec: 773026500 }

writer instance: Instant { tv_sec: 1627237, tv_nsec: 773026500 }

writer instance: Instant { tv_sec: 1627237, tv_nsec: 773026500 }

writer instance: Instant { tv_sec: 1627237, tv_nsec: 773026500 }

We can see that the instance before and after the reset is different, and there’s no trace of the existing writer instance after the reset. We can sleep well knowing that our reset works and there isn’t a lonely actor out there without a purpose (in our system, that is—we cannot vouch for Hollywood).

Summary

In this chapter, we built a system that accepts key-value transactions, backs them up with a writer actor, and is monitored via a heartbeat mechanism. Even though this system has a lot of moving parts, the implementation was simplified by the router pattern. The router pattern is not as efficient as directly calling an actor, as the message has to go through one actor before hitting its mark. However, the router pattern is an excellent starting point. You can lean on the router pattern when figuring out the actors you need to solve your problem. Once the solution has taken form, you can then move toward actors directly calling each other as opposed to going through the router actor.

While we focused on building our entire system by using actors, we must remember that they are running on an async runtime. Because actors are isolated and easy to test because they communicate only with messages, we can take a hybrid approach with actors. This means that we can add additional functionality to our normal async system using actors. The actor channel can be accessed anywhere. As with the migration from the router actor to actors directly calling one another, you can slowly migrate your new async code from actors to standard async code when the overall form of the new async addition takes form. You can also use actors to break out functionality in legacy code when trying to isolate dependencies to get the legacy code into a testing harness.

In general, because of their isolated nature, actors are a useful tool that you can implement in a range of settings. Actors can also act as code limbo when you are still in your discovery phase. We’ve both reached for actors when having to come up with solutions in tight deadlines such as caching and buffering chatbot messages in a microservices cluster.

In Chapter 9, we continue our exploration of how to approach and structure solutions with our coverage of design patterns.